- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

November 13, 2017

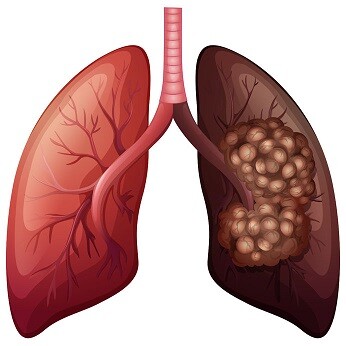

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths for both men and women in the United States. However, for people who are diagnosed at an early stage of the disease, surgery can often be performed to achieve a cure. If your health care team has suggested that you might be able to receive a lung operation to treat your cancer, you may be experiencing a lot of mixed emotions. Of course, it is common to be encouraged by the possibility of a curative treatment. At the same time, an upcoming surgical procedure can be a stressful and an overwhelming time of uncertainty. It can be challenging to separate the facts regarding your operation from many of the common myths.

Myth #1: Exposing the tumor to air will make it spread.

Truth: This old wives’ tale consists of inaccurate information that has been widely believed in some circles. The fact is that air does not make tumors spread, and surgical resection is the best chance of a cure for many people with early stage lung cancer. Of course, a properly conducted operation is critical to the overall outcome of the procedure. We recommend finding a thoracic surgeon who specializes in lung cancer surgery. Participation in the STS General Thoracic Database is a sign that your surgeon is interested in meeting standards of care regarding quality outcomes.

Myth #2: Surgery for lung cancer is an emergency to prevent the disease from spreading.

Truth: It is important to initiate a plan of care as soon as reasonably possible. However, it’s also key that you receive the right treatment for your stage of disease and for your body (based on any other medical issues you may have). Your doctors may need a few weeks to properly identify your stage of disease and to perform other tests, such as lung function tests and cardiac clearance, to ensure that you are safe for surgery. It’s much better to have a brief delay prior to initiating proper therapy rather than rushing into the wrong treatment plan. It is normal to expect that your operation might be scheduled within a month of your diagnosis. Delays of more than a couple of months could result in disease progression; waits of a few weeks are typical and safe.

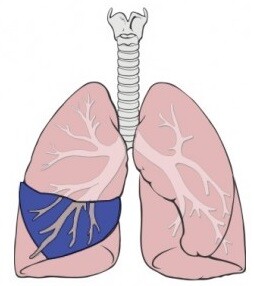

Myth #3: After lung cancer surgery, patients who have had portions of their lungs removed need to be on home oxygen.

Truth: It is not common for patients to require long-term oxygen after surgery. You will complete lung function tests prior to undergoing surgery, and your surgeon will calculate the expected impact on your lung function after surgery. This will depend on how much lung you need to have removed for the best chance for cure. While removal of one of the five lung lobes is the most common operation performed for lung cancer, some patients may need more lung removed because of the size or location of the tumor. Other patients may be offered smaller operations if their lung function is not as good, in order to reduce risk of having difficulty breathing after surgery. You should realize that almost all patients are on oxygen for the first day or two after surgery, and the majority are off oxygen before leaving the hospital. Sometimes, patients go home on temporary oxygen following surgery, but it is not permanent. Your surgeon can discuss with you the risk of long-term oxygen use and shortness of breath, based on the results of your own lung function tests.

Myth #4: You will not be able to participate in normal activities after lung cancer surgery.

Truth: It is an expected goal that patients will return to their normal life activities following lung cancer surgery. Many individuals may feel particularly tired the first 1-2 weeks after surgery, but it is still safe to be home alone, care for oneself, be out in public, socialize, and perform light household duties. In fact, walking every day and being active are important to a healthy recovery. Physical activity will help minimize risk of certain complications like blood clots and pneumonia. It is possible to return to certain occupations in the early postoperative period, depending on whether your job involves strenuous activities and whether your job will allow any flexibility for light duties or shortened hours. In general, many surgeons limit how much you can lift for about a month after surgery, so that is an important consideration. However, you should be able to drive as long as you are not taking narcotic pain medications. You should be able to function fairly independently after hospital discharge, short of lifting heavy objects.

Myth #5: If you already have cancer, it doesn’t matter if you keep smoking.

Truth: It is incredibly important to stop smoking prior to surgery! Continuing smoking dramatically increases your risk of complications after surgery, including pneumonia, respiratory failure, and other infections. It’s very important that your body is able to use its natural defenses to clear secretions from your lungs after surgery. Even one cigarette can paralyze the cilia in your lungs and airways for up to 3 weeks, impairing your body’s ability to bring up problematic phlegm from deep in your lungs. This risk can be substantially reduced by completely quitting smoking at least 3 weeks prior to surgery. Your doctor may be able to refer you to a tobacco cessation program.

Myth #6: Lung cancer surgery requires being admitted to an ICU and staying on a ventilator.

Truth: While this may have been true in the past, most lung operations do not require these measures. In fact, we know that patients do much better if we remove the breathing tube and wake up the patients in the OR at the end of the procedure. Of course, there are exceptions, and each situation must be considered on a case-by-case basis. But overall, staying on a ventilator in an ICU is not the norm after lung surgery.

Myth #7: All lung cancer operations can be performed with a thoracoscopic approach or with a robot.

Truth: There are a number of caveats as to whether an operation can be performed with particular instruments or technology, related to the tumor size, location, and other patient-specific factors. While not all operations can be completed thoracoscopically or robotically, it is still possible to have less invasive incisions. You can ask your surgeon if he/she plans to cut the muscles and ribs. In addition, even with larger incisions, it is still possible to use enhanced recovery pathways that get patients back on their feet faster. These issues are definitely worth discussing with your surgical team.

Myth #8: The surgeon will be able to tell you exactly how long the operation will take, how long you’ll be in the hospital, and which day you will be able to go home.

Truth: We can provide overall ranges of how long operations and hospital stays typically take, but every patient is different. While we understand that it’s helpful for patients and their families to plan for duration of hospitalization, it’s most important that you are not released until it is safe to do so. Sometimes patients meet goals for discharge earlier than expected, and sometimes it takes longer than expected. In general, the criteria for being able to go home will include having normal vital signs, normal labs, being able to urinate and walk independently, having adequate pain control, and in some cases, awaiting removal of a chest drainage tube. You can ask your surgical team what specific criteria they have for you before you’d be able to leave the hospital. This is often more helpful than a guess as to the total number of days needed.

Myth #9: After you’ve had lung cancer surgery, you won’t see your thoracic surgeon any longer.

Truth: Patients usually are scheduled for a postoperative visit about a month after surgery to check on how the recovery is going. This visit typically includes an exam and a chest x-ray. If you have any problems related to your surgery before your postoperative visit, it’s actually very important that you contact your surgeon, rather than seeking care elsewhere. Sometimes, other doctors may not be familiar with the normal postoperative appearance of chest imaging or of surgical incisions. Your surgeon will best be able to help make sure that your recovery is going as planned. After the initial recovery period, surgeons often will continue to follow their patients for visits and imaging studies to ensure that the cancer doesn’t come back, as the greatest risk for recurrence is in the first 2 years. Most surgeons like to stay involved with their patients after surgery.

Myth #10: If you have a lung cancer operation, there would not be any reason to ever undergo chemotherapy or radiation.

Truth: Unfortunately, in some circumstances, patients need additional therapy even if the operation was successful. This is because we know that larger tumors or those that have spread to lymph nodes have a greater chance of coming back, even after a complete operation. Your need for additional therapies will depend heavily on the final pathology interpretation of the tissue that is removed at the time of the operation. The surgeon will discuss with you the findings from the tissue that was examined under a microscope. If the tumor is over a certain size, you might be recommended to receive chemotherapy. If any lymph nodes were found to have cancer, you will likely be recommended to have chemotherapy, and it may additionally require radiation, depending on which lymph nodes. Overall, the goal is to try to do everything possible to provide a cure, and the strategy for achieving a cure will be variable depending on your exact stage of disease.

As you can see, while there is an abundance of information available regarding lung cancer surgery, not all of it is accurate. It’s incredibly important to be able to delineate the realities from the rumors. If you have any doubts or concerns about anything that you’ve heard, seen, or read, check with your treatment team! They will be able to help clarify any questions and guide you to the most accurate information.

Read more about lung cancer.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons.