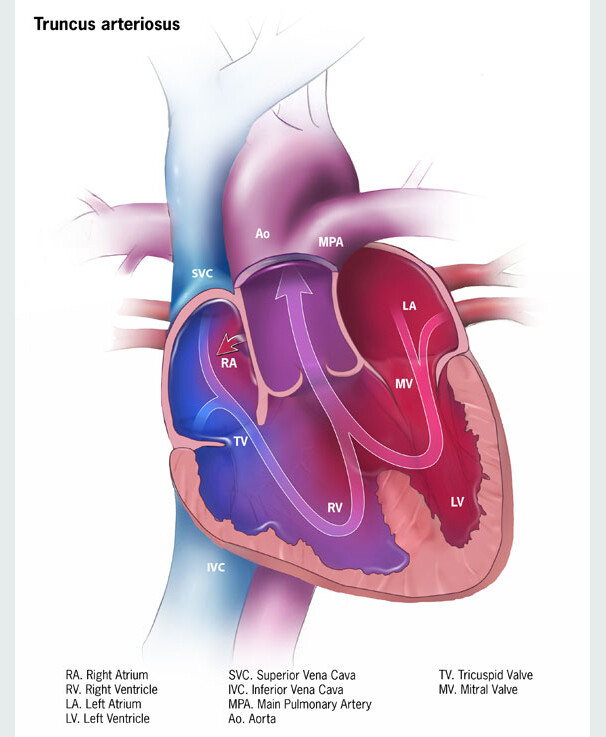

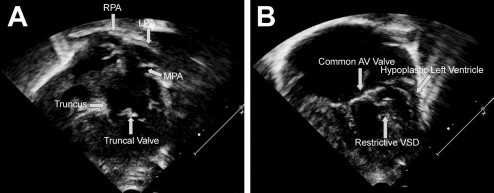

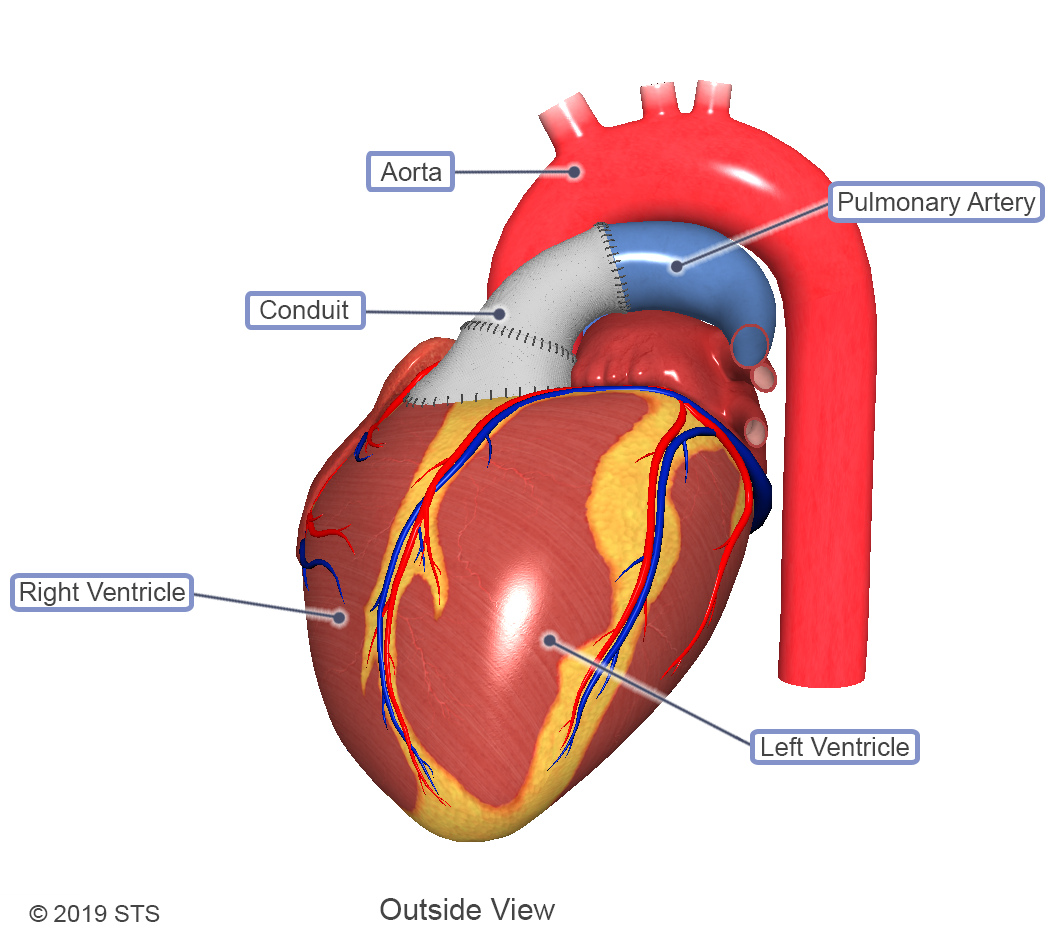

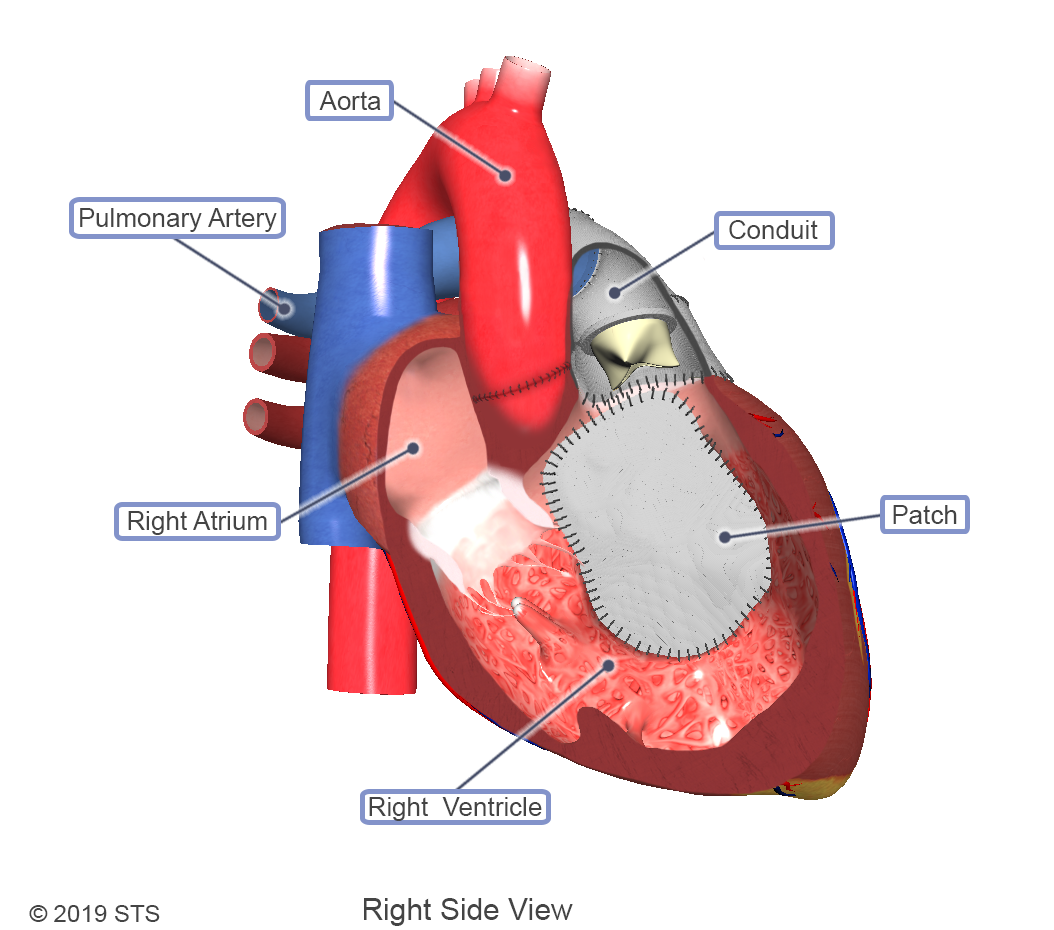

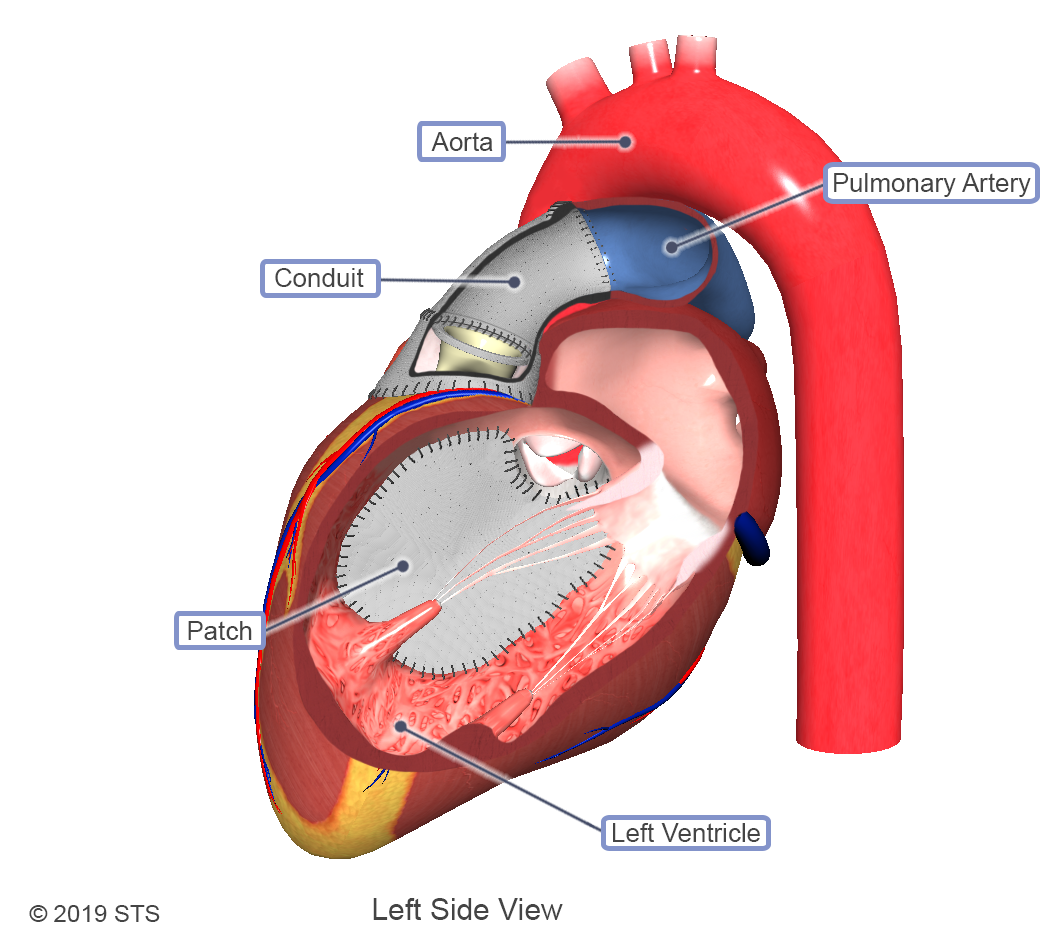

Cases of truncus arteriosus can vary depending on how the pulmonary arteries exit the aorta. Along with the different types, varying levels of complexity exist within this one diagnosis. With truncus arteriosus, a large hole is usually found between the two ventricles (ventricular septal defect), which causes oxygen-poor (blue) blood and oxygen-rich (red) blood to mix together; too much blood goes to the lungs, and the heart works harder to pump blood to the rest of the body.

The truncal valve is often abnormal with this disease. It can be thickened and narrowed, which can block the blood as it leaves the heart, or it can leak, causing blood that leaves the heart to leak back into the heart across the valve. The presence of narrowing and leaking is a predictor of poorer outcomes.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), truncus arteriosus occurs in fewer than one out of every 10,000 live births, which means that about 300 babies are born with truncus arteriosus each year in the United States.