- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

What is an LVAD?

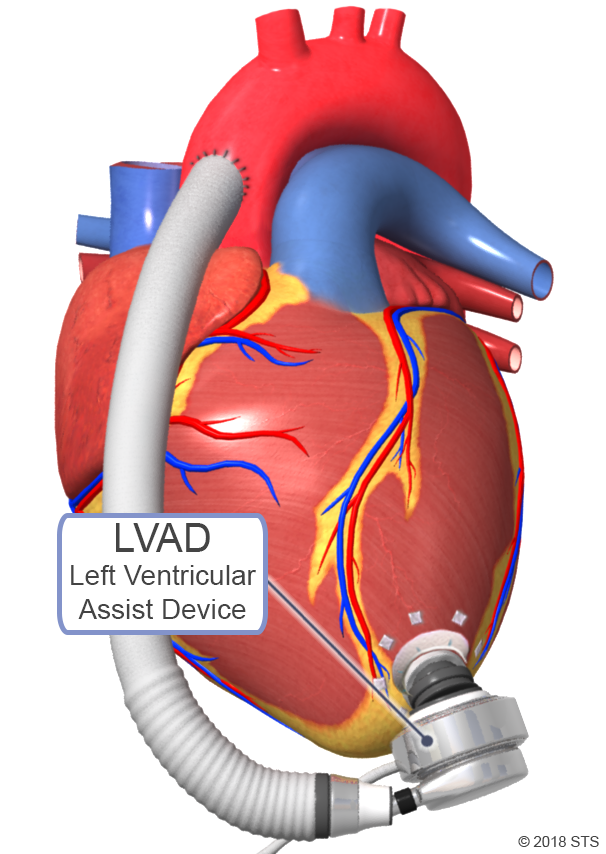

Like the heart, the left ventricular assist device (LVAD) pumps blood to the body. This battery-operated, mechanical device is surgically implanted inside a person's chest, just below the heart. The LVAD doesn't replace the heart; instead, it helps maintain the pumping ability of a heart that is too weak to work on its own. The device supports the main pumping chamber (left ventricle) by moving blood to the rest of the body.

The LVAD is used for patients who have severe heart failure and don’t improve with medications and for those who are waiting for a heart transplant. Patients who receive an LVAD often experience less fatigue, more strength, and better breathing, as well as longer survival. The American Heart Association estimates that there are currently 50,000 to 100,000 advanced heart failure patients in the US who could benefit from an LVAD, without which most would have decreased chance of survival and significantly limited lifestyles.

One end of the LVAD is attached to the apex or tip of the left ventricle, while the other end is connected to the aorta (the body’s main artery). Blood flows through the heart into the LVAD which continuously pumps blood to the rest of the body.

While there are a few different types of LVADs available, all of which are portable, each system generally has four main parts:

- HEART PUMP—connected to the left side of the heart; moves blood from the heart to the rest of the body.

- BATTERIES—provide power when the system is not plugged into an outlet.

- DRIVELINE—a cable that transfers power and information between the controller and the heart pump.

- CONTROLLER—powers and checks the pump and driveline; provides alerts on how the system is working.

Having an LVAD implanted requires open heart surgery, which usually takes 4 to 6 hours. The LVAD is placed inside the body, in the upper part of the abdomen (just below the heart), with the driveline attached to the pump. The tube is brought out of the abdominal wall to the outside of the body and attached to the pump’s battery and controller.

When the LVAD battery is running low, an alarm sounds to let you know that it needs to be changed. Two power sources are always connected to the controller. This way, if one battery runs down, there is another available to power the LVAD for several more hours. The batteries last for approximately 12 hours, and must be recharged at night. The external controller and batteries may be carried in a shoulder bag, backpack, or on a belt/harness along with the necessary backup equipment.

The LVAD can be used in two ways:

BRIDGE-TO-TRANSPLANT: LVADs support heart failure patients who are waiting for a donor heart to become available. The pump allows the heart and other body systems to rest and grow stronger while waiting for the heart transplant surgery. The amount of time with an LVAD as a bridge-to-transplant depends on the medical condition, blood type, and body size.

DESTINATION THERAPY: LVADs provide long-term support for patients with advanced-stage heart failure who do not respond to conventional therapy and are not good candidates for heart transplantation. The goal of destination therapy is to support heart function and improve quality of life for the rest of the patient’s life.

Patients with LVADs can be discharged from the hospital, return to normal activities, and enjoy a good quality of life while waiting for a donor heart to become available. Destination therapy patients also can experience improved quality of life for years after LVAD implantation.

To determine if an LVAD is the best treatment, you will be evaluated by an LVAD/heart transplant selection committee. The team may consist of:

- Heart failure cardiologists

- Cardiothoracic surgeons

- Nurse practitioners and physician assistants

- Social workers

- Bioethicists

- Palliative medicine specialists

- Cardiac rehabilitation specialists

- Dietitians

- Other specialists, such as lung or kidney physicians

In order to receive an LVAD device, several tests are performed to determine if you are a good candidate for surgery. Tests may include routine blood work, chest x-ray, electrocardiogram (EKG), echocardiogram, left and right heart catheterization, as well as carotid and peripheral ultrasounds, routine health screenings such as colonoscopy or mammogram, and a psychosocial/psychiatric evaluation.

When all testing and evaluations are completed, the cardiologist presents your case to the selection committee, who determines whether an LVAD is a safe and appropriate therapy for you.

As with any surgical procedure, there are risks involved with the LVAD operation. Your physician will discuss with you the specific risks and potential benefits of the LVAD implantation. Some of the possible risks include bleeding, development of blood clots, heart failure, respiratory failure, kidney failure, stroke, infection, and device failure.

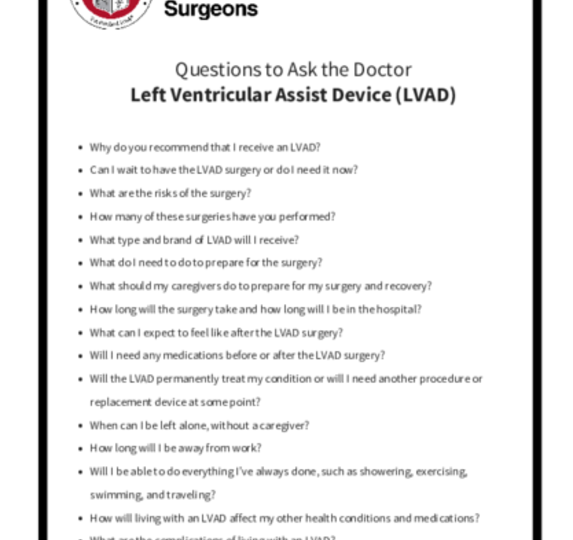

When you meet with your physician, ask questions to make sure you understand why the LVAD is recommended and the potential risks of the operation.

After the implantation procedure, you and your caregivers will receive LVAD training, with detailed instructions to ensure safe and proper use of the LVAD. You’ll learn how to manage the device and troubleshoot potential emergency situations. Members of your LVAD team will help you understand:

- How the device works

- What the alarms mean

- Proper system maintenance

- Daily, weekly, monthly, and annual procedures

- How to monitor for changes

- When to notify the LVAD team of changes or issues

Before you are discharged from the hospital, you must demonstrate your knowledge about the device and may be given a test by your care team. You’ll also need to establish independence with self-care activities, so physical and occupational therapists will work with you to build up your strength. In addition, you can expect to meet with a dietician to discuss a “heart healthy” diet now that you have a LVAD.

The goal is to make sure you go home as soon as possible but, on average, patients remain in the hospital for 14 to 21 days. Discharge timing will depend on your physical recovery, medical condition, and familiarity with caring for the LVAD. Some patients stay in an intermediate care facility or rehabilitation center until they are fully ready to return home.

Medications after LVAD

Your physician may prescribe a combination of different medications to support your overall health and heart function, and to prevent complications related to the LVAD. Every patient has different medication needs, based on current health status and medical history. It’s your job to take your medication regularly and exactly as directed.

In general, all LVAD patients take blood thinners (warfarin) and aspirin to help prevent blood clots from forming inside the pump. You also can expect to be on many of the same medications you were taking for heart failure, including beta blockers, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and diuretics (water pills).

Recovering and returning to routine daily activities after receiving an LVAD is a gradual process. After receiving an LVAD, you will be able to perform most activities. You can shower, bicycle, hike, and even return to work, in some cases. You also can travel, with minor accommodations. You must keep your equipment with you at all times (not checked in cargo), and your route and destination should include areas with an LVAD program, just in case of an emergency.

LVAD patients cannot swim or take a bath, play contact sports, lift heavy weights, or be away from an electrical power source.

It’s very important to make healthy lifestyle choices before and after receiving your LVAD, including:

- Quitting tobacco use

- Eating a “heart healthy” diet

- Stopping alcohol use

- Not using illegal drugs

- Exercising regularly

If you need help making lifestyle changes, talk to your physician.

It is not uncommon to experience anxiety or depression when you receive an LVAD or when you become a caregiver for an LVAD recipient. If you are feeling especially worried or stressed, reach out to your treatment team, family, and friends. You also may want to consider joining an LVAD support group or talking with a professional counselor.

Reviewed by: Amy E. Hackmann, MD, and Muhammad Faraz Masood, MD

August 2018