- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

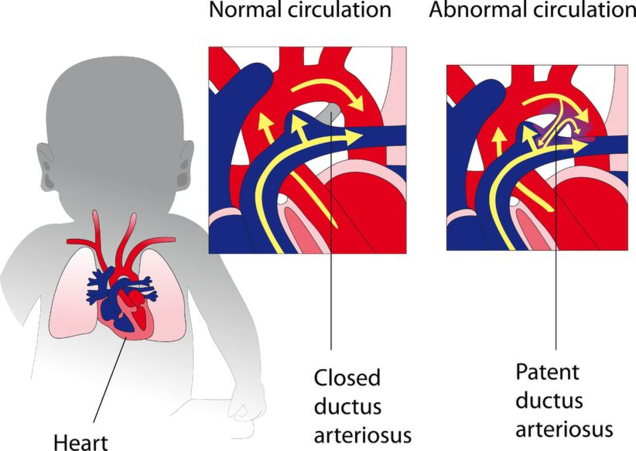

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is a congenital heart defect that occurs soon after birth in some babies.

Before birth, the baby receives oxygen via the mother's lungs and placenta. As a result, the baby’s own blood does not need to circulate between the heart and lungs for oxygenation. The ductus arteriosus is an open blood vessel or “tube” that allows the blood to skip the lungs and instead flow directly to the body.

Soon after your baby is born and takes his or her first breath, the lungs open up and blood begins to flow through, picking up oxygen. At this point, the ductus arteriosus is no longer needed. Under normal circumstances, the ductus arteriosus closes within the first few days after birth and blood no longer passes through it. However, in some babies, the ductus arteriosus remains open, or “patent.”

How does PDA affect the heart?

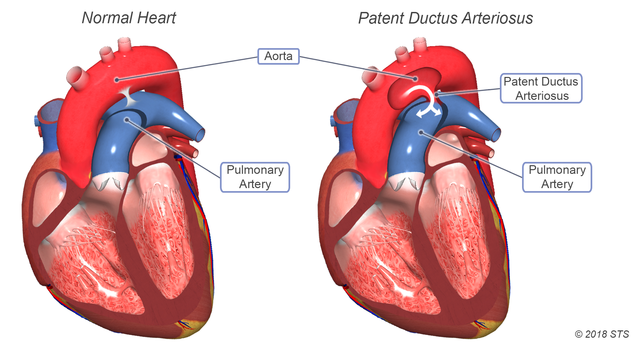

Normally, the artery on the heart's left side (aorta) pumps blood to the body only and the artery on the right side (pulmonary artery) pumps blood to the lungs only. In a child with PDA, the blood gets mixed. If the PDA is large, the mixed blood makes the heart and lungs work harder and the lungs can become congested.

PDA is a fairly common congenital heart defect in the United States. Although the condition can affect full-term infants, it's more common in premature infants. On average, PDA occurs in about 8 out of every 1,000 premature babies, compared with 2 out of every 1,000 full-term babies, according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Causes

While in most children, the cause of PDA is not known, the most common association is prematurity. PDA also can occur in combination with other heart defects.

PDA is more common in:

- Infants who have genetic conditions such as Down syndrome.

- Infants whose mothers had German measles (rubella) during pregnancy.

- Girls (PDA is twice as common in girls as it is in boys).

Symptoms

The symptoms associated with PDA vary, depending on the size of the defect, how much blood it carries, and whether the baby is full term or premature.

A small PDA may cause no signs or symptoms. However, PDA may still cause a distinctive heart murmur that is heard during a physical exam. A heart murmur is an extra or unusual sound heard during the heartbeat. Heart murmurs also have other causes besides PDA.

A large PDA can cause signs of congestive heart failure soon after birth. The extra blood flow from the aorta into the lungs can overload the lungs and put additional burden on the heart. This may not be well tolerated, especially in premature babies. These babies may breathe faster and harder than normal and need help from a ventilator. Other common symptoms include:

- Shortness of breath

- Rapid pulse

- Poor feeding and poor weight gain

- Sweating with exertion, such as while feeding

- More frequent respiratory infections

It’s important to note that even when there are no symptoms, the turbulent flow of blood through the PDA puts a baby at a higher risk for a serious infection, known as endocarditis. Endocarditis is an infection of the inner lining of the heart chambers and heart valves.

In full-term infants, PDA usually is first suspected when the doctor hears a heart murmur during a regular checkup. Premature babies who have PDA may not have the same signs as full-term babies, such as heart murmurs. Instead, PDA in premature babies may cause breathing problems and other symptoms of heart failure.

If the doctor suspects that your child has PDA, he or she may refer you to a pediatric cardiologist—a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating heart problems in children. Tests can help confirm a diagnosis:

Chest X-ray

A chest X-ray may be necessary to see the condition of a baby’s heart and lungs.

Echocardiogram (echo)

An echocardiogram (echo) is a painless test that uses sound waves to create a moving picture of your baby’s heart. In babies who have PDA, echo shows how big the PDA is, the flow of blood through the PDA, and if the heart chambers have become enlarged due to the extra blood flow. Echo is the most common method to diagnose PDA. In addition, when medical treatments are used to close the PDA, echo is used to see how well the treatments are working.

For more information on these tests, visit our common diagnostic tests page.

PDA may be treated with medicines, catheter-based procedures, and surgery. The goal of treatment is to close the PDA. Closure will help prevent complications and reverse the effects of increased blood volume going to the lungs. The risk of complications with any of these treatments is low, determined mostly by how ill your child is prior to treatment.

Small PDAs often close without treatment within the first few months of life. For full-term infants, treatment is needed if the PDA is large or causing health problems. For premature infants, treatment is needed if the PDA is causing breathing problems or heart problems.

Talk with your child’s doctor about treatment options and how your family prefers to handle treatment decisions.

The doctor may prescribe medications to help close your child's PDA.

In premature babies, indomethacin is often used to help close the PDA. When given intravenously, this medication triggers the PDA to constrict or tighten, which closes the opening. Indomethacin may have side effects, such as kidney injury, intestinal tears or bleeding, so not all babies can receive it. Because of the potential side effects, the baby must have lab values checked before medications are administered. If the lab values are not normal or if the medication does not work, surgery may be performed. This type of treatment is typically only effective in newborns.

Sometimes, children who have PDAs are given medicine to keep the ductus arteriosus open. For example, this may be done if a child is born with another heart defect that decreases blood flow to the lungs or the rest of the body. Keeping the PDA open helps maintain blood flow and oxygen levels until doctors can perform surgery to correct the other heart defect.

The doctor may prescribe medications to help close your child's PDA.

In premature babies, indomethacin is often used to help close the PDA. When given intravenously, this medication triggers the PDA to constrict or tighten, which closes the opening. Indomethacin may have side effects, such as kidney injury, intestinal tears or bleeding, so not all babies can receive it. Because of the potential side effects, the baby must have lab values checked before medications are administered. If the lab values are not normal or if the medication does not work, surgery may be performed. This type of treatment is typically only effective in newborns.

Sometimes, children who have PDAs are given medicine to keep the ductus arteriosus open. For example, this may be done if a child is born with another heart defect that decreases blood flow to the lungs or the rest of the body. Keeping the PDA open helps maintain blood flow and oxygen levels until doctors can perform surgery to correct the other heart defect.

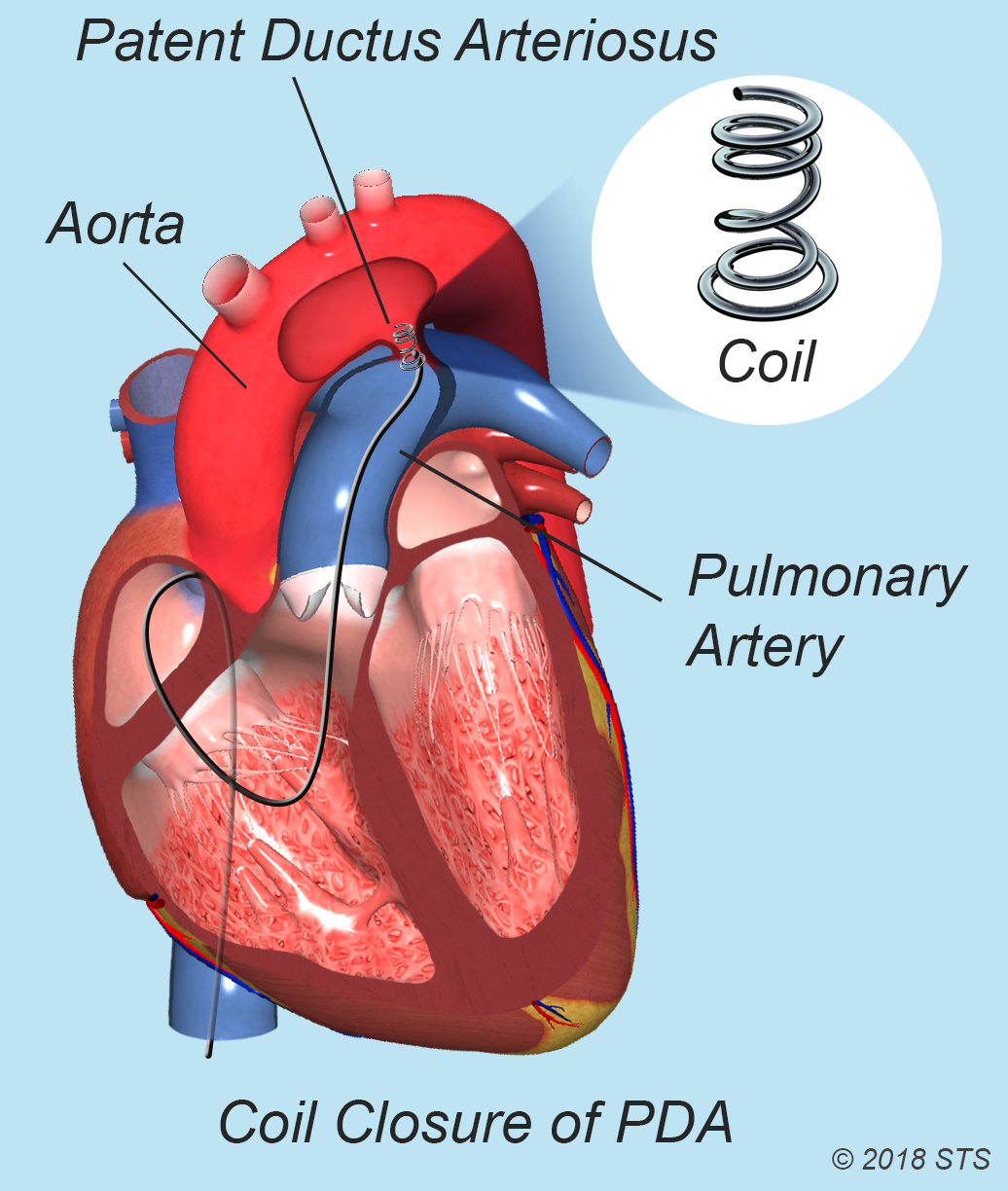

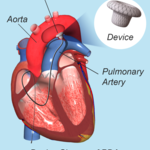

In an infant or child with a small PDA, your doctor may recommend a catheter-based procedure or “transcatheter device closure.”

During the procedure, your child will be given medicine to help him or her sleep during the procedure. It also is possible that he or she will be placed under general anesthesia (depending on age). The doctor will insert a catheter in a large blood vessel in the upper thigh and guide the catheter to your child's heart. A small metal coil or other blocking device is passed through the catheter and placed in the PDA. This device acts as a plug and blocks blood flow through the vessel.

Catheter-based procedures don't require major incisions, allowing your child to recover quickly. These procedures often are done on an outpatient basis. You'll most likely be able to take your child home the same day the procedure is done.

Complications from catheter-based procedures are rare and short term. They can include bleeding, infection, and movement of the blocking device from where it was placed.

In an infant or child with a small PDA, your doctor may recommend a catheter-based procedure or “transcatheter device closure.”

During the procedure, your child will be given medicine to help him or her sleep during the procedure. It also is possible that he or she will be placed under general anesthesia (depending on age). The doctor will insert a catheter in a large blood vessel in the upper thigh and guide the catheter to your child's heart. A small metal coil or other blocking device is passed through the catheter and placed in the PDA. This device acts as a plug and blocks blood flow through the vessel.

Catheter-based procedures don't require major incisions, allowing your child to recover quickly. These procedures often are done on an outpatient basis. You'll most likely be able to take your child home the same day the procedure is done.

Complications from catheter-based procedures are rare and short term. They can include bleeding, infection, and movement of the blocking device from where it was placed.

Surgery may be recommended if:

–A premature or full-term infant has health problems due to a PDA and is too small to have a catheter-based procedure.

–A catheter-based procedure doesn't successfully close the PDA.

–The PDA is large or doesn’t close on its own.

–Surgery is planned for treatment of related congenital heart defects.

For surgical procedures, your doctor may prescribe antibiotics to prevent bacterial infection after leaving the hospital.

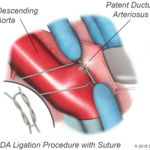

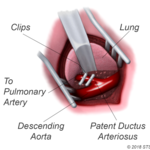

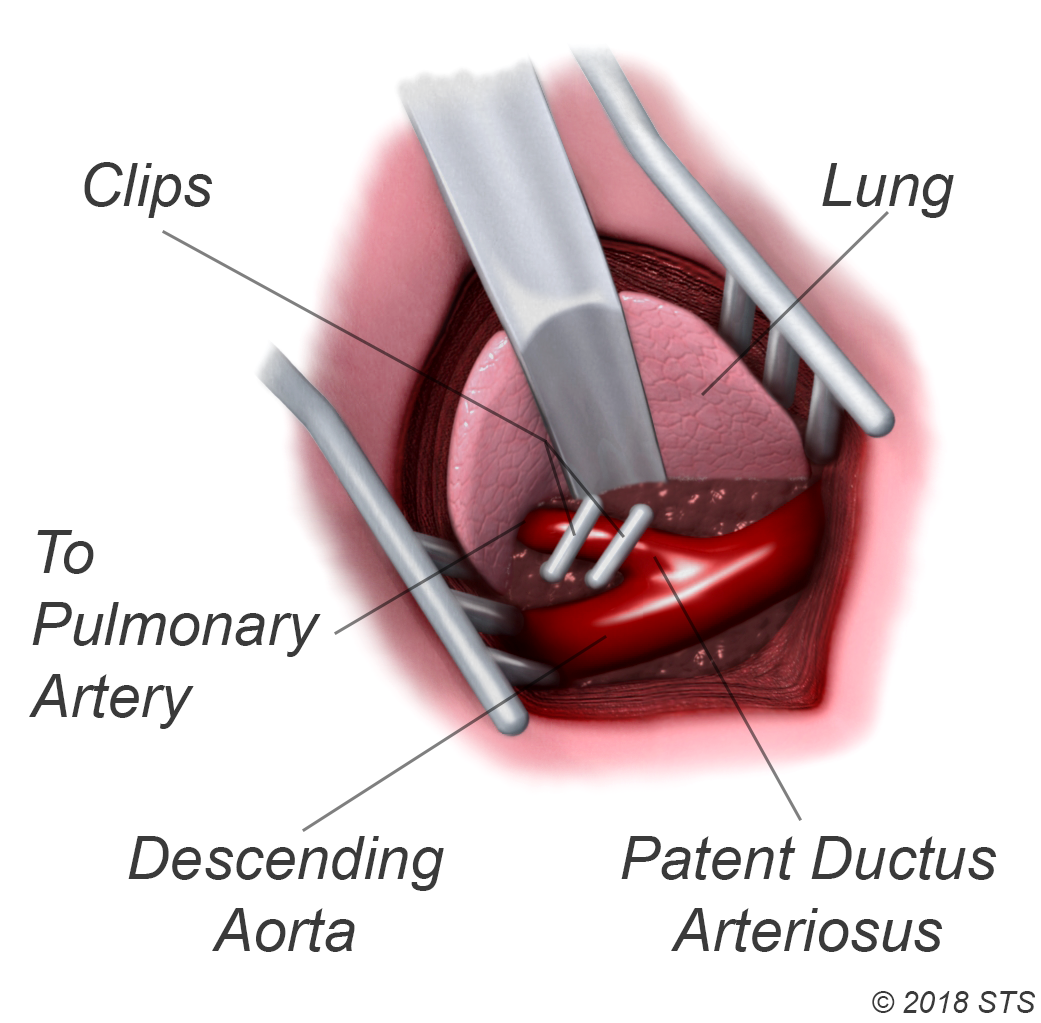

For the surgery, your child will be given medication so that he or she will sleep and not feel any pain. The surgeon will make a small incision between your child's ribs on the left side. The PDA is closed by tying it with thread-like material (suture) or by permanently placing a small metal clip around the ductus to squeeze it closed. If there's no other heart defect, this restores the child's circulation to normal.

Complications from surgery are rare and usually short term. They can include hoarseness, a paralyzed diaphragm (the muscle below the lungs), infection, bleeding, or fluid buildup around the lungs.

Surgery may be recommended if:

–A premature or full-term infant has health problems due to a PDA and is too small to have a catheter-based procedure.

–A catheter-based procedure doesn't successfully close the PDA.

–The PDA is large or doesn’t close on its own.

–Surgery is planned for treatment of related congenital heart defects.

For surgical procedures, your doctor may prescribe antibiotics to prevent bacterial infection after leaving the hospital.

For the surgery, your child will be given medication so that he or she will sleep and not feel any pain. The surgeon will make a small incision between your child's ribs on the left side. The PDA is closed by tying it with thread-like material (suture) or by permanently placing a small metal clip around the ductus to squeeze it closed. If there's no other heart defect, this restores the child's circulation to normal.

Complications from surgery are rare and usually short term. They can include hoarseness, a paralyzed diaphragm (the muscle below the lungs), infection, bleeding, or fluid buildup around the lungs.

After Surgery

After surgery for PDA, your child will spend a few days in the hospital. He or she may be given medicine to reduce pain and anxiety. Most full-term children who undergo elective PDA surgery go home within 2 days after surgery. Premature infants usually have to stay in the hospital longer because of other health issues.

The doctors and nurses at the hospital will teach you how to care for your child at home and will discuss:

- Limits on activity for your child while he or she recovers

- Follow-up appointments with your child’s doctors

- How to give your child medications at home, if needed

When your child goes home after surgery, you can expect that he or she will feel comfortable and should begin to eat better and gain weight quickly.

Image

Living With/Life After PDA

Most children who have PDAs live healthy, normal lives after treatment, without any special restrictions on physical activity. Within a few weeks, he or she should fully recover and be able to take part in normal activities.

Full-term infants will likely have normal activity levels, appetite, and growth after PDA treatment, unless they had other congenital heart defects. For premature infants, the outlook after PDA treatment depends on other factors, such as how early the child was born and whether other illnesses or conditions are present.

Depending on the type of PDA closure, your child’s pediatric cardiologist may examine it periodically to look for uncommon problems. Long-term complications are rare. However, they can include narrowing of the aorta, incomplete closure of the PDA, and reopening of the PDA.

Most infants will make a complete recovery, with no additional need for medicines, surgery, or catheterization.

Reviewed by: Lauren Kane, MD, and Ram Kumar Subramanyan, MD, PhD

April 2018