- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

Typically, old or damaged cells die and new, normal cells (the building blocks that make up the tissue and organs in the body) take their place. But sometimes, the process goes wrong and abnormal cells start to grow. These cells crowd out the normal cells and form a mass of tissue called a tumor. Tumors can be benign, which means that they are noncancerous and not life threatening. Other times, tumors are cancerous (malignant) and can invade surrounding tissues or spread to other areas of the body.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates that more than 234,000 new cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed and more than 154,000 patients will die from lung cancer in 2018. Lung cancer accounts for 27% of all cancer deaths and is the leading cause of cancer deaths among both men and women. Each year, more people die of lung cancer than colon, breast, and prostate cancers combined.

Lung cancer occurs mainly in older people. Two out of three people diagnosed with lung cancer are age 65 years or older. Most people who are diagnosed with lung cancer are current or former smokers. Younger people who have never smoked also can be diagnosed with lung cancer, though this is rare.

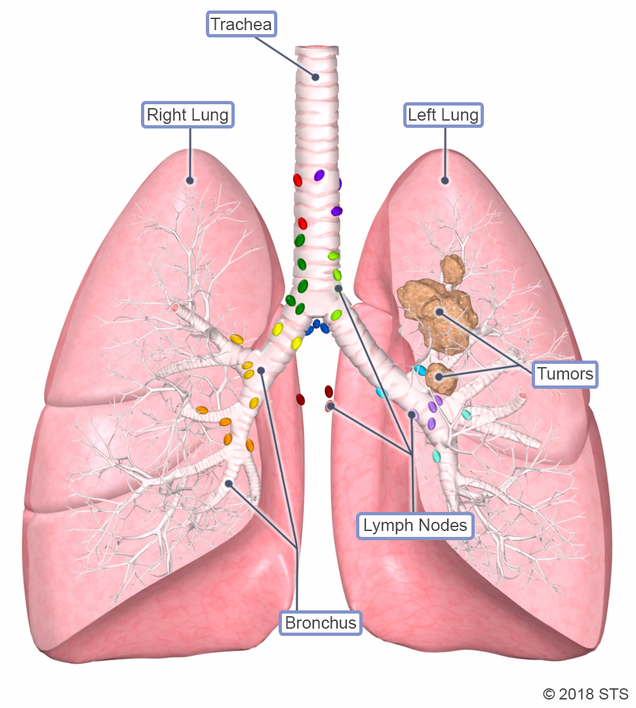

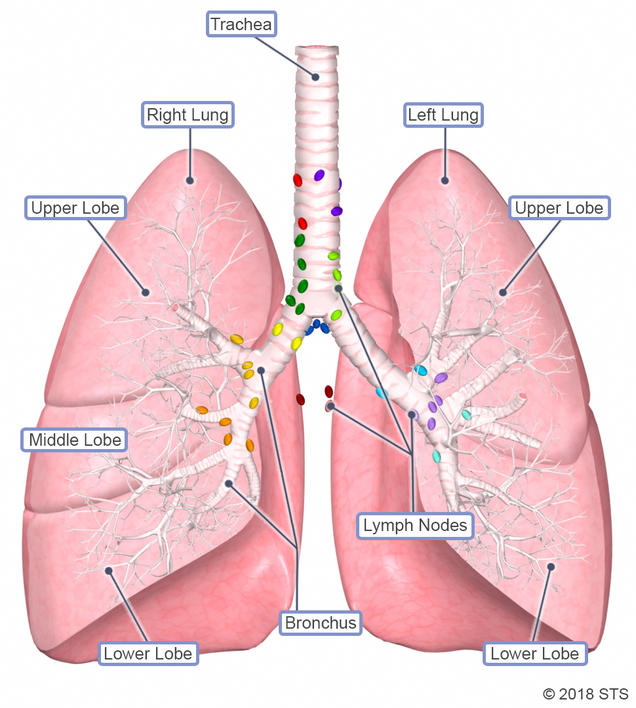

LUNG AND AIRWAY ANATOMY

The lungs are the organs that allow for the essential exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between us and the air that we breathe. Inhaling toxins from the environment (cigarette smoke, dust, industrial toxins) can contribute to lung diseases, such as lung cancer, emphysema, and pulmonary fibrosis. This is because the lungs are some of the only organs in direct contact with the environment (the skin is another one).

Humans have two lungs: right and left. The lungs exchange air via passages that connect to the nose and mouth called airways. The largest pipe that connects directly to the nose and mouth is called the trachea (also known as the windpipe). The trachea divides in two airways (right mainstem bronchus that goes to the right lung and left mainstem bronchus that goes to the left lung). The right lung has three large sections called lobes: upper, middle, and lower. The left lung has two lobes: upper and lower. The lobes are separated into smaller sections called segments.

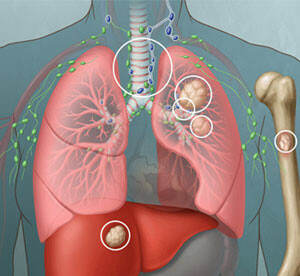

The lymph nodes are small organs that are located throughout the body and look like islands. They contain cells that fight infection, inflammation, or cancer. We have lymph nodes inside the lungs (in between segments and in between lobes) and outside the lungs (hilar nodes surrounding the mainstem bronchus and mediastinal nodes in the middle of the chest).

TYPES OF LUNG CANCER

Cancer in the lungs can be primary (originates in the lung) or can start in other organs and spread to the lungs. When cancers from other organs spread to the lungs, the tumors are called metastases.

The three main types of lung cancer are: Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), small cell lung cancer (SCLC), and lung carcinoid tumors.

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

The most common type of lung cancer is NSCLC, which accounts for about 83% of lung cancers. It is named non-small-cell lung cancer because, under a microscope, the cells are larger than small-cell lung cancer. While there are many types of NSCLC, the two most common types are adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC)

About 13% of all lung cancers are SCLC, characterized by the appearance of small cells when seen under a microscope. This type of cancer is diagnosed almost exclusively in heavy smokers. It usually is treated with chemotherapy and radiation; however, surgery may be an option for small tumors that have not spread to the lymph nodes.

SCLC often starts in the bronchus (the airways of the lung), near the center of the chest. It tends to spread quickly to the lymph nodes and other areas of the body.

Lung carcinoid tumor

Carcinoid tumors of the lung account for fewer than 5% of lung tumors. They are made up of neuroendocrine cells, which sometimes produce hormones. Most are slow-growing tumors and usually can be cured by surgery. Sometimes carcinoid tumors develop inside the airway and may require complex surgery to remove while sparing the lung tissue.

Cancers that spread to the lungs

Cancers that start in other organs of your body (like the colon or kidney) can sometimes spread (metastasize) to the lungs, but these are not true lung cancers. For example, cancer that starts in the colon and spreads to the lungs is still colon cancer; it has just spread to your lungs. Treatment for metastatic cancer to the lungs is based on where it started (the primary cancer site), the involvement of other areas of the body (such as the liver or brain), and the size, number, and location of the nodules. Metastatic tumors from certain cancers, like colon and kidney cancers, can be limited to the lung and removal can improve outcomes, whereas other cancers tend to spread widely throughout the body and should be treated with chemotherapy rather than surgery.

CAUSES AND RISK FACTORS

Smoking, present or past, is the single greatest risk factor for lung cancer. Cigar and pipe smoking are almost as likely to cause lung cancer as cigarette smoking. The ACS estimates that 80% to 85% of all lung cancer cases in the United States are a result of smoking.

Smokers are 25 times more likely than non-smokers to have lung cancer, and the longer you smoke and the more packs a day you smoke, the greater your risk. Even if you smoke low-tar or “light” cigarettes, you are still at risk. No one knows for sure the impact of vaping and smoking e-cigarettes on lung health. E-cigarettes contain nicotine. Like tobacco cigarettes, they can lead to nicotine addiction. Some claim that inhaling e-cigarettes may be safer than tobacco smoking. There are no data to support these claims.

Research shows that quitting smoking at any time of your life decreases your risk.

Regular exposure to secondhand smoke also increases your risk for developing lung cancer. It is estimated that secondhand smoke causes more than 3,000 lung cancer deaths each year among nonsmoking adults. A growing body of evidence shows that lung cancer rates are increasing in non-smokers.

In addition, other harmful substances, such as radon, can cause lung cancer. Radon is a naturally occurring odorless, tasteless, invisible radioactive gas that can seep out of the ground. The amount of radon coming from the ground varies from area to area. People exposed to high radon levels are more likely to get lung cancer. In fact, radon exposure is a leading cause of lung cancer in nonsmokers. Radon levels can be high in underground mines and in tightly sealed, poorly ventilated homes, generally those with basements. Air pollution and other environmental toxins such as arsenic, diesel exhaust, asbestos (a mineral-based substance once used in insulation and building construction), beryllium, uranium, and silica also have been linked to lung cancer.

Researchers are learning that certain genetic mutations are linked to lung cancer. Mutations are genes that work differently than their “normal” versions. People who have those genes may be more likely to get lung cancer. Having one of these genes may be why some non-smokers get lung cancer.

Other causes/risk factors for lung cancer include:

- A history of cancer in another part of the body. People with a history of head and neck cancer or esophageal cancer, both associated with tobacco use, are at higher risk. People who have had breast, colon, or prostate cancer, are at increased risk.

- Age. Lung cancer risk increases with age. Only about 10% of cases occur in people younger than 50.

- Family history. If one of your family members has had lung cancer, your risk may increase. Be sure to let your doctor know if you have a parent, sibling, or child with lung cancer.

- Prior radiation therapy. Radiation is an important cancer treatment. Radiation to the chest area, especially for treatment of another cancer, seems to increase the risk.

- Other lung disease. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), interstitial lung disease, emphysema, and tuberculosis (TB) may increase lung cancer risk. Scarring of the lungs from other diseases may set the stage for lung cancer.

Having more than one risk factor increases your odds of developing lung cancer. A smoker with asbestos exposure has about four times the risk of developing lung cancer as a smoker without it. It’s 80 times the risk compared with someone who neither smoked nor was exposed to asbestos.

SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of lung cancer can affect the whole body. Any persistent, unusual, or unexplained symptom should be checked out by a doctor. A constant cough and shortness of breath are the most common. Everyone coughs sometimes, but a cough that persists—especially with other signs, such as blood in the mucus or unexplained pain—should always be checked out. However, many patients with lung cancer have no symptoms at all. Like all cancers, lung cancer is best treated when caught early.

Other common symptoms include:

- Coughing up blood

- Chest, shoulder, or back pain

- Voice changes, especially hoarseness

- Repeated lung infections (such as pneumonia or bronchitis)

- Difficulty swallowing

If lung cancer spreads beyond the lungs to other parts of the body, you may experience symptoms, including weakness, fatigue, unexplained weight loss, bone or joint pain, unexplained broken bones, headaches, blood clots or bleeding, unsteady movement or seizures, memory loss, and neck or face swelling.

If you are experiencing any symptoms that cause you to worry, make an appointment to see your doctor. You can expect your health care team to ask you many questions about your health. Not only will they take a full medical history, but they also will perform a thorough physical exam. Tests will be ordered to assess the cause of any symptoms you may be experiencing.

DIAGNOSIS

Most lung cancers are often found during radiology scans performed for other reasons. These imaging studies include chest x-ray, computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron emission tomography (PET scan). For more information on these tests, visit our common diagnostic tests page.

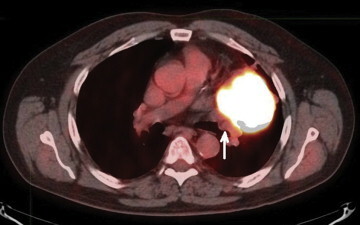

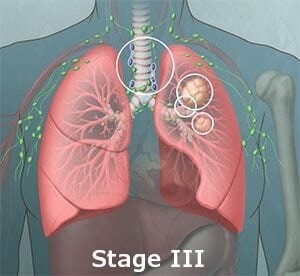

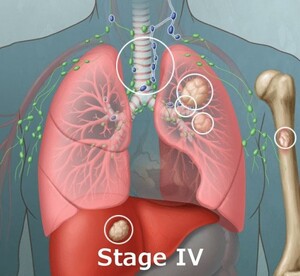

If a tumor/mass suspicious for lung cancer is found on a chest CT, your doctor may order a PET scan to evaluate if the cancer has spread. If there is suspicion for primary lung cancer that has spread outside of the chest, a biopsy is usually performed from the distant site of disease, which would confirm stage IV lung cancer. Similarly, if there is suspicion for primary lung cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes in the middle of the chest (mediastinal lymph nodes), a biopsy would be obtained from the mediastinal lymph nodes, which would confirm stage III disease. In other words, a biopsy typically is obtained from the site that would give the higher stage. This helps determine the type of treatment for lung cancer.

PET scan showing mass in left upper lobe

If a single tumor is found without spread to lymph nodes or distant sites, then the type of biopsy required to make a diagnosis of lung cancer would depend on the location of the tumor and how well fit you are for thoracic surgery. In good surgical candidates, tumors near lung surface (peripheral) less than 3 cm may go directly to surgery without requiring a needle biopsy.

Even though imaging studies may be suggestive of lung cancer, only a biopsy can confirm the diagnosis. During a lung biopsy procedure, your doctor removes a small piece of tissue or fluid from the chest so it can be examined under a microscope to check for cancer cells. Your doctor can perform a biopsy in a number of ways, depending on the location of the cancer and your overall condition. The types of biopsies include:

- Bronchoscopy (Transbronchial Biopsy): Your cardiothoracic surgeon or interventional pulmonologist puts a small, flexible tube into your mouth or nose and then into your lungs. A light and camera help guide tiny tools that take cells from your lung out through the tube.

- Lung Needle Biopsy (Transthoracic Biopsy): You usually get this type of lung biopsy when cells can’t be reached with a bronchoscopy. An interventional radiologist places a needle through your chest between two ribs to take a sample from the outer area of your lungs.

- Thoracoscopic Lung Biopsy (Thoracoscopy): While you are under general anesthesia, your doctor makes up to three small cuts on your chest between your ribs, then puts a thin, lighted tube with a camera on the end and uses tiny tools to pull out some cells.

- Open Lung Biopsy (Limited Thoracotomy): This biopsy is usually only used when other methods can’t get cell samples. While you are under general anesthesia, your surgeon makes an incision that runs from your chest and under your arms to your back. He/she is then able to reach your lungs and remove the cells.

Your lung biopsy sample will be sent to a lab, and you should expect to get results within a week. The results will show what type of lung cancer you have and can help determine your prognosis and guide treatment.

What Are the Stages of Lung Cancer?

Once lung cancer has been diagnosed, your doctor will use a biopsy or imaging studies such as a CT scan, MRI, and a PET scan, to determine the stage of the cancer. The stage will help you understand where the tumor or cancer cells are located in your lungs, how large the tumor is, and if the cancer has spread. Classification is different for NSCLC vs SCLC. Knowing the stage also helps you and your doctor decide what treatment is most appropriate, as different stages of lung cancer receive different treatments. For example, some advanced stages of lung cancer do not benefit from surgical intervention.

Lung cancer staging often uses the letters T, N, and M: Though the TNM system seems complicated, it is based on three major factors.

- T stands for the tumor’s size and where it’s located in the lungs or body.

- N stands for node (lymph node) involvement. This indicates whether or not the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes near the lungs.

- M stands for metastasis. This means whether or not the cancer has spread from where it originated in the lung to other organs. Lung cancer can spread to the other lung or the liver, bones, brain, kidneys, adrenal glands, or other parts of the body.

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

The most common way to stage an NSCLC tumor is by using the TNM system with the numbers X, 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 after each letter. This helps your doctor determine the most effective therapy, per recommendations from organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Your doctor also may use the TNM system in combination with the general stages for NSCLC:

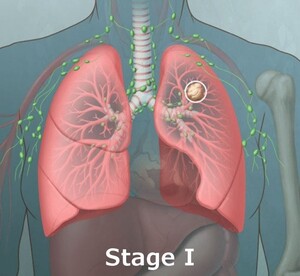

Stage 0: The tumor is very small and has not spread into the deeper lung tissues or outside the lungs.

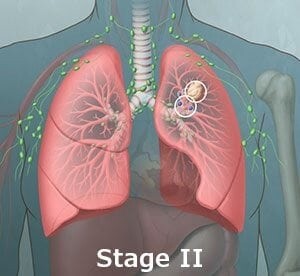

Stage I: The single tumor, typically small, is in the lung tissue, but has not spread to the lymph nodes.

Stage II: The single tumor may be larger than a stage 1 tumor or has spread to lymph nodes within the same lung.

Stage III: The single tumor may have spread to the mediastinal lymph nodes or lymph nodes in the middle of the chest, in between both lungs. Stage IIIA disease usually involves lymph nodes on the same side as the cancer, whereas Stage IIIB usually there is spread of tumor to lymph nodes on the opposite side of the chest or above the collarbone.

Stage IV: Cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the liver, bones, or brain.

Small Cell Lung Cancer

If you have this type of cancer, your doctor may use the TNM system, in addition to one of these main stages:

Limited – Stage I-III: The cancer is in just one lung and possibly nearby lymph nodes, but hasn’t spread to both lungs or past the lungs. This type can be safely treated with definitive radiation doses. Excludes multiple nodules that are too large to tolerate radiation.

Extensive – Stage IV Cancer: The cancer has spread to other areas of the lungs and chest and may have spread to the fluid around the lungs (called the pleural fluid) or other organs. This type also may include multiple nodules in one lung that are too large to tolerate radiation.

WHO SHOULD BE SCREENED FOR LUNG CANCER?

Screening means testing to find a disease before it causes any symptoms or problems, especially in people who are at a higher risk of getting a disease. In the case of lung cancer, a cure is possible with early diagnosis and treatment with surgery, so screening can be critically important.

Annual screening is recommended for people who meet all of the following criteria:

- Are between ages 55 – 80 years old

- Have no signs or symptoms of lung cancer

- Smoke now or have quit smoking within the last 15 years

- Have a tobacco smoking history of at least 30 pack years (1 pack year = smoking one pack per day for 1 year or two packs a day for 15 years)

The recommended screening test is a low-dose CT scan, or LDCT. During an LDCT scan, you lie on a table and an x-ray machine scans your body, using a low dose (amount) of radiation to make detailed pictures of your lungs. The scan only takes a few minutes and is not painful.

Private insurance plans cover lung cancer screening for people age 55 through 80, usually with no out-of-pocket costs. Medicare pays for an annual lung cancer screening with no out-of-pocket costs for people up to age 77 if you meet the following criteria:

- You must have a written order from your health care professional (your doctor, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant).

- Your visit with your health care professional must be a “shared decision-making visit.” In this visit, your health care professional must use one or more decision aids and discuss benefits and harms of an LDCT. Your health care professional must also talk about follow-up diagnostic testing, overdiagnosis, false alarms, and total radiation exposure from screening.

- You must go to a screening facility that participates in the lung cancer screening registry set up for Medicare patients.

After the initial screening exam, there may be additional costs for follow-up tests and/or treatments. Contact your insurance company to see if the procedures are covered and what your costs would be.

Making the decision to be screened for lung cancer is a personal decision. You should talk with your health care professional and choose what is right for you. For more information, read “Lung Cancer Screening,” from Douglas E. Wood, MD.

TREATMENT

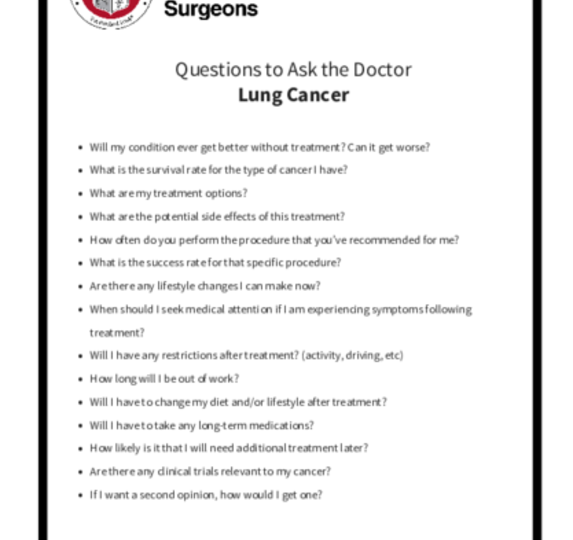

Lung cancer treatment depends on the type of lung cancer, the stage, and whether it contains any specific features (biomarkers). Cardiothoracic surgeons play a very important role in the treatment of lung cancer. Your surgeon and the rest of your health care team also will consider your overall health and wishes when planning your treatment. You can print these sample questions to use as a basis for discussion with your doctor.

For early stage lung cancer, surgery is usually the most effective treatment to completely remove the cancerous cells along with the affected lymph nodes. If the disease is more advanced, patients are often treated with chemotherapy or combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy in conjunction with surgery.

Surgery

To determine whether you are a good candidate for surgery, you need to undergo pulmonary function testing. Depending on your symptoms and risk factors, cardiac testing to evaluate your heart also may be performed.

During surgery, your surgeon works to remove the lung cancer and a margin of healthy tissue. The amount of lung to be removed depends on the location and stage of the tumor and your overall health before surgery. Keeping yourself in good health, stopping smoking, and being active will reduce your chance of complications and make recovery after surgery much easier.

For more information about preparing for surgery and what to expect on the day of, see Before Lung Cancer Surgery and Day of Lung Cancer Surgery.

Procedures to remove lung cancer include:

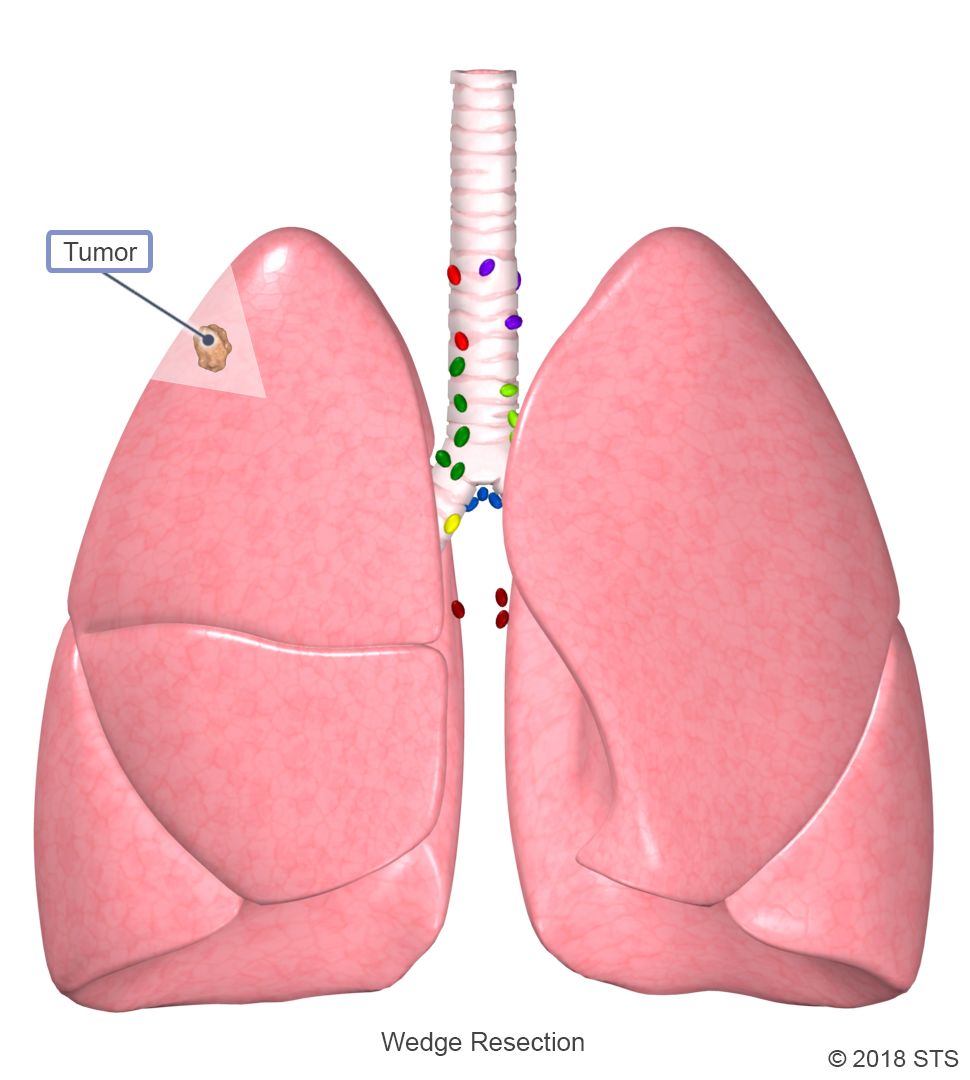

A wedge resection is a procedure that involves the surgical removal of a small, wedge- or pie-shaped piece of the lung. This procedure removes only the cancerous part of the lobe, rather than the entire lobe.

A wedge resection is performed if the cancer is contained within a small area. It may be recommended for carcinoid tumors and metastatic nodules that have spread from other cancers, and certain subtypes of slow-growing NSCLC. This surgery also is preferred for patients with a significant decrease in lung function who cannot tolerate the removal of a large-sized section of the lung. A wedge resection is often done in conjunction with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.

A cardiothoracic surgeon may perform a wedge resection by minimally invasive video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), robotic-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (RATS), or by a thoracotomy (open chest surgery) and typically requires 1 to 3 days in the hospital.

A wedge resection is a procedure that involves the surgical removal of a small, wedge- or pie-shaped piece of the lung. This procedure removes only the cancerous part of the lobe, rather than the entire lobe.

A wedge resection is performed if the cancer is contained within a small area. It may be recommended for carcinoid tumors and metastatic nodules that have spread from other cancers, and certain subtypes of slow-growing NSCLC. This surgery also is preferred for patients with a significant decrease in lung function who cannot tolerate the removal of a large-sized section of the lung. A wedge resection is often done in conjunction with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.

A cardiothoracic surgeon may perform a wedge resection by minimally invasive video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), robotic-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (RATS), or by a thoracotomy (open chest surgery) and typically requires 1 to 3 days in the hospital.

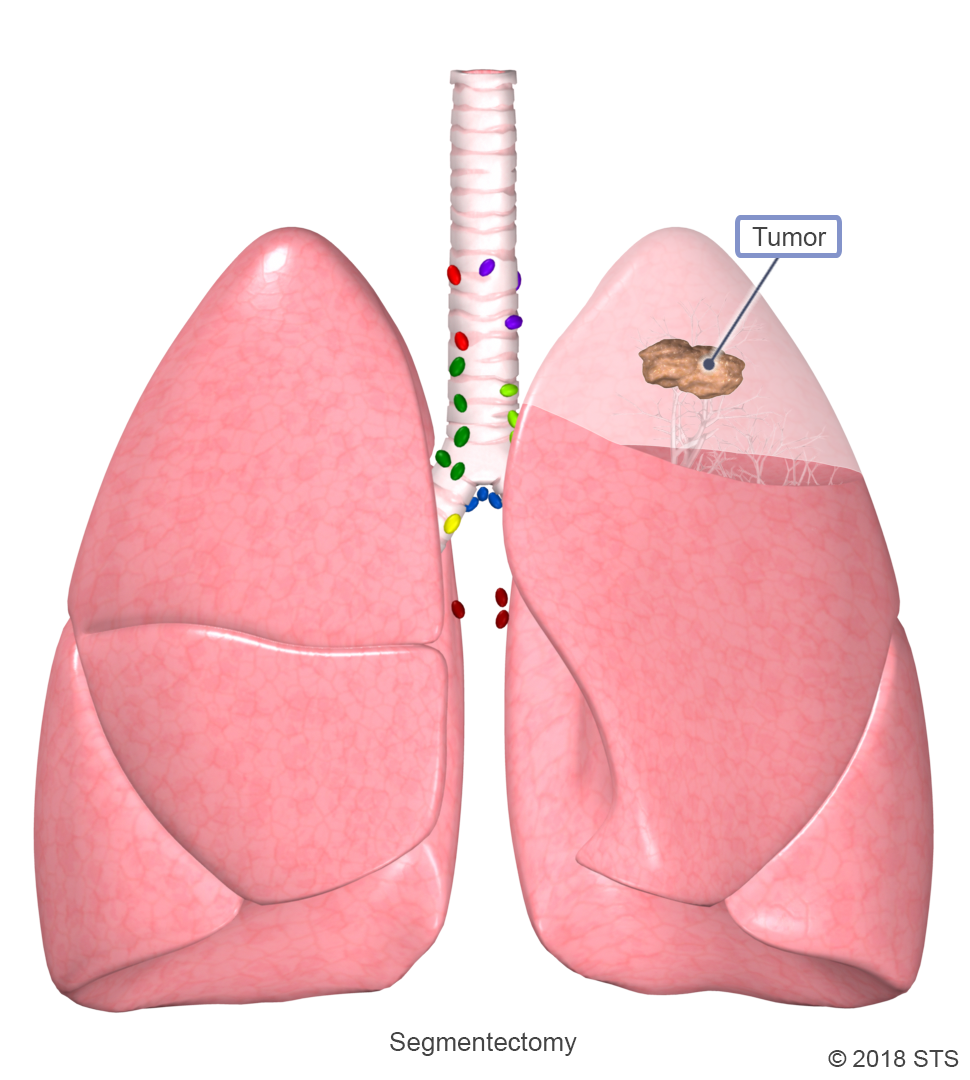

The right lung has three lobes and the left lung has two lobes. The lobes are separated into smaller sections called segments, with each lobe containing between 2 and 5 segments. Segmentectomy, or segment resection, is a surgical treatment that removes one or more segments but less than the entire lobe of the lung. In general, segmentectomy is only recommended for patients with early stage NSCLC.

Segmentectomy can be performed through a thoracotomy, RATS, or by VATS and typically requires 3 to 4 days in the hospital.

The right lung has three lobes and the left lung has two lobes. The lobes are separated into smaller sections called segments, with each lobe containing between 2 and 5 segments. Segmentectomy, or segment resection, is a surgical treatment that removes one or more segments but less than the entire lobe of the lung. In general, segmentectomy is only recommended for patients with early stage NSCLC.

Segmentectomy can be performed through a thoracotomy, RATS, or by VATS and typically requires 3 to 4 days in the hospital.

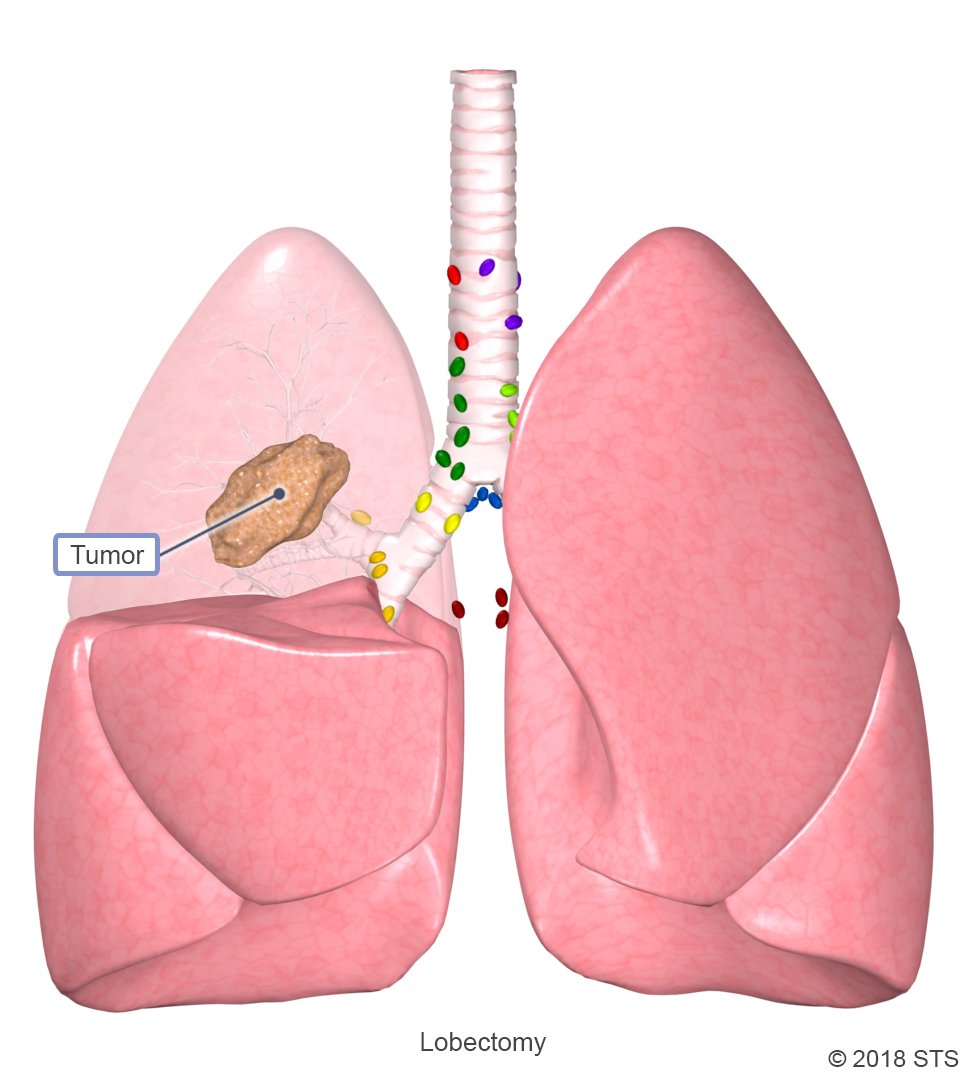

With a lobectomy, a cardiothoracic surgeon will remove an entire lobe of the lung. After the surgery, the healthy tissue inflates to make up for the missing section, so the lungs should work as well or better than they did before. Lobectomy is the most common and preferred type of treatment for people with early stages of NSCLC, when there’s a tumor in just one part of the lung. In these cases, lobectomy offers the best chance for a cure and may be the only treatment you need.

Lobectomy is most often performed through a thoracotomy, RATS, or VATS and typically requires 4 to 6 days in the hospital.

With a lobectomy, a cardiothoracic surgeon will remove an entire lobe of the lung. After the surgery, the healthy tissue inflates to make up for the missing section, so the lungs should work as well or better than they did before. Lobectomy is the most common and preferred type of treatment for people with early stages of NSCLC, when there’s a tumor in just one part of the lung. In these cases, lobectomy offers the best chance for a cure and may be the only treatment you need.

Lobectomy is most often performed through a thoracotomy, RATS, or VATS and typically requires 4 to 6 days in the hospital.

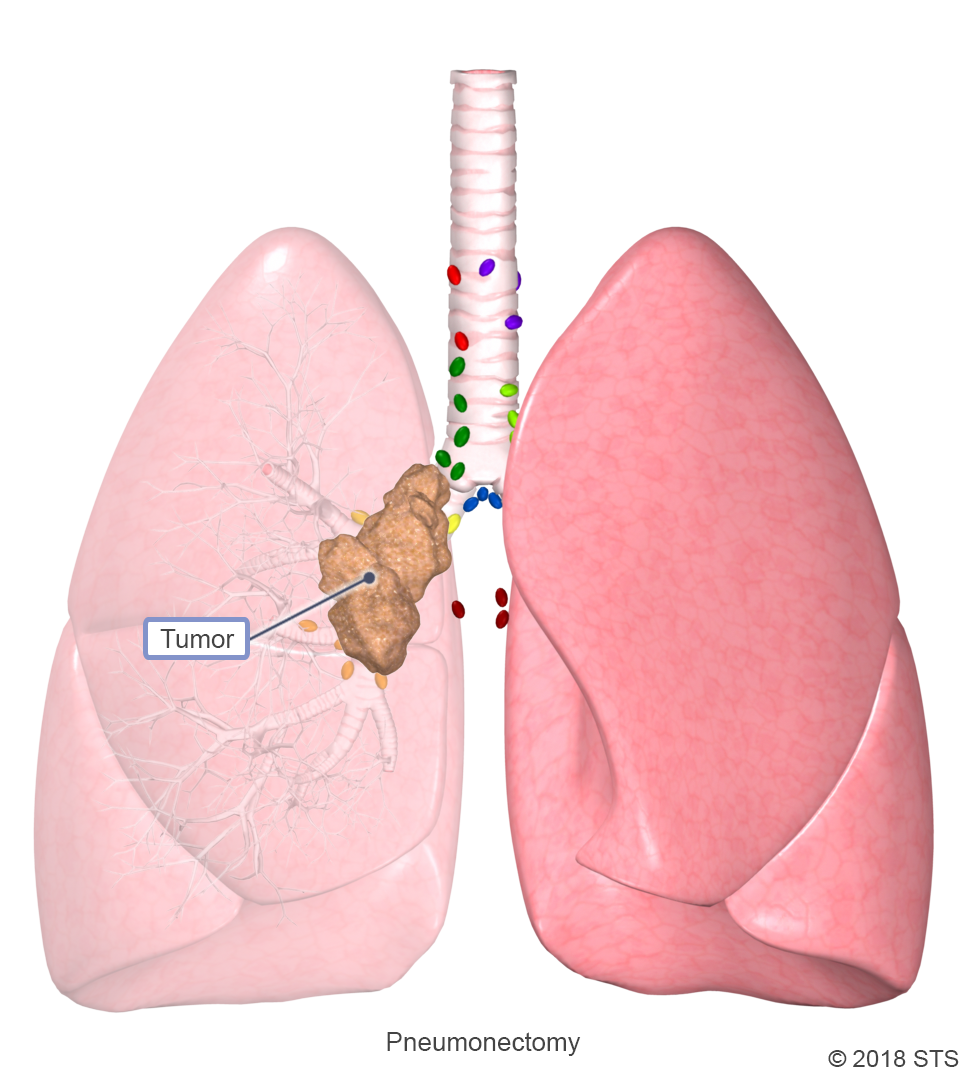

A pneumonectomy is a type of lung cancer surgery in which an entire lung is removed. This surgery is most commonly done as a treatment for NSCLC, when a less invasive procedure, such as a lobectomy, cannot remove the entire tumor. This may occur if the tumor is large, if it has spread beyond a single lobe, or if it is located in the central area of the lungs. In preparing for a pneumonectomy, tests will then be done to make sure you have adequate lung function and will be able to tolerate living with only one lung.

This extensive procedure is usually performed by a thoracotomy and typically requires 5 to 7 days in the hospital.

A pneumonectomy is a type of lung cancer surgery in which an entire lung is removed. This surgery is most commonly done as a treatment for NSCLC, when a less invasive procedure, such as a lobectomy, cannot remove the entire tumor. This may occur if the tumor is large, if it has spread beyond a single lobe, or if it is located in the central area of the lungs. In preparing for a pneumonectomy, tests will then be done to make sure you have adequate lung function and will be able to tolerate living with only one lung.

This extensive procedure is usually performed by a thoracotomy and typically requires 5 to 7 days in the hospital.

A sleeve lobectomy is the removal of a complete lobe of the lung as well as part of the airway that moves air to the remaining lobe. The airway and remaining lobe are then reconnected so that they can continue to function. This procedure may avoid the need for pneumonectomy.

Sleeve lobectomy can be performed by a thoracotomy and typically requires 5 to 7 days in the hospital.

A sleeve lobectomy is the removal of a complete lobe of the lung as well as part of the airway that moves air to the remaining lobe. The airway and remaining lobe are then reconnected so that they can continue to function. This procedure may avoid the need for pneumonectomy.

Sleeve lobectomy can be performed by a thoracotomy and typically requires 5 to 7 days in the hospital.

Chest wall resection involves the partial or full surgical removal of soft tissue, cartilage, sternum and/or ribs. The need for chest wall reconstruction—using prosthetic materials to rebuild the skeletal structure of the chest wall—depends on the size and location of the defect. Chest wall tumor involvement occurs in less than 10% of patients with NSCLC.

This procedure is performed by a thoracotomy and typically requires 5 to 7 days in the hospital.

Chest wall resection involves the partial or full surgical removal of soft tissue, cartilage, sternum and/or ribs. The need for chest wall reconstruction—using prosthetic materials to rebuild the skeletal structure of the chest wall—depends on the size and location of the defect. Chest wall tumor involvement occurs in less than 10% of patients with NSCLC.

This procedure is performed by a thoracotomy and typically requires 5 to 7 days in the hospital.

An operation for lung cancer is a major surgery. Following the operation, if your lungs are in good condition, you can usually return to normal activities after a period of recovery, even if a lobe or an entire lung has been removed. Total time for recovery is different for every patient and depends on the condition of your lungs prior to surgery and any complications experienced after the operation.

It is common to experience pain, weakness, fatigue, and shortness of breath after surgery. You also may have problems moving around, coughing, and breathing deeply. While in the hospital, it is important that you work on deep breathing and coughing to keep your lungs functioning. You should walk as soon as possible after surgery and spend most of the day sitting upright in the chair to expand your lungs.

During most surgical procedures, you will have a chest tube inserted to help drain excess air and fluid and to help your lungs re-inflate. It’s likely that this tube will remain in place for a few days. When the tubes are all removed and your scars are improving, keep in mind that there is significant healing that still needs to take place inside your body.

Possible complications depend on the extent of the surgery and your overall health. Problems can include excess bleeding, infections, and pneumonia. The vast majority of patients do not experience any serious complications and can return to a normal life in a couple of weeks.

For more details on what to expect, read “What Patients Should Know About Life After Lung Cancer” from Dr. Leah Backhus, and “You’ve Had Lung Cancer Surgery: Now What?” from Dr. Mara Antonoff.

For more information about recovery, visit After Lung Cancer Surgery.

Reviewed by: Loretta Erhunmwunsee, MD, and Nestor R. Villamizar, MD

October 2018