Ventricular Septal Defect

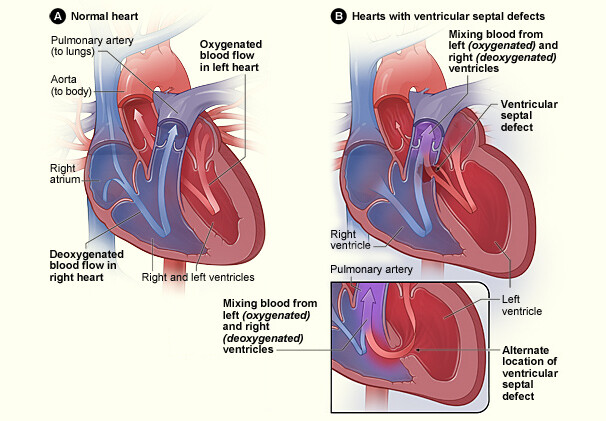

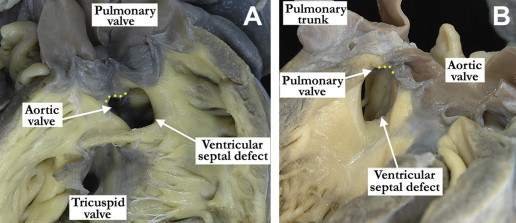

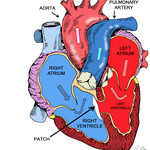

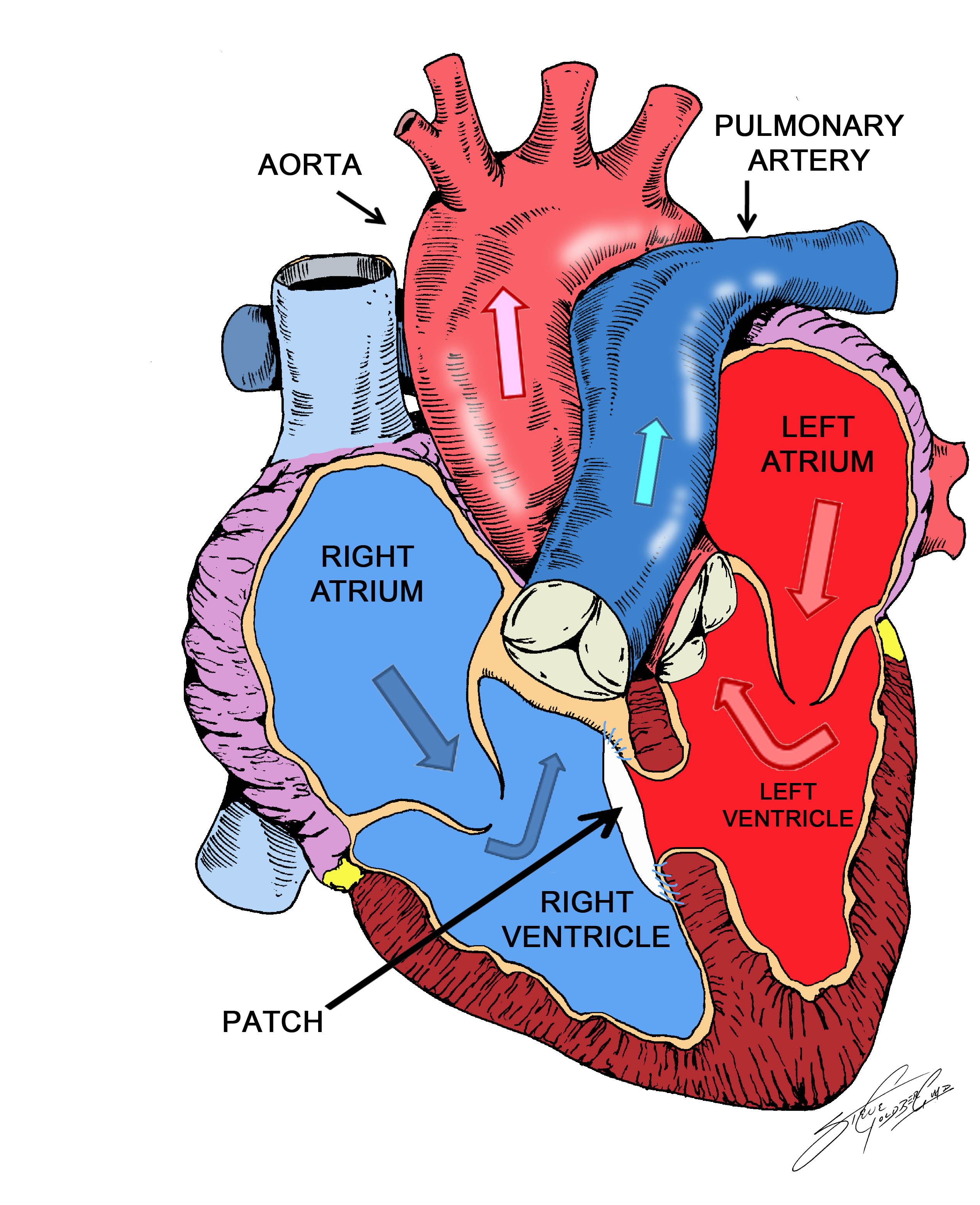

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a hole in the wall (septum) that separates the lower chambers of the heart. It is often referred to as “a hole in your heart.” The hole allows blood to pass from the left side of the heart to the right side, causing oxygen-rich (red) blood to get pumped back to the lungs instead of out to the body, which makes your heart work harder.

According to the American Heart Association, congenital heart defects (present at birth) are the most common type of birth defect. They affect 8 out of every 1,000 newborns. Each year, more than 35,000 babies in the United States are born with congenital heart defects.

VSDs are among the most common, accounting for 20% to 30% of all congenital heart defects. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 42 out of every 10,000 babies born have a VSD.

VSDs can be diagnosed through a routine physical examination with your child’s physician. Most often, the physician will hear a heart murmur during the exam and order additional testing, such as an echocardiogram (echo).

Children who have a VSD that closed on its own or closed completely with surgery do not need any medications and should not be restricted in any way.