- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

Some babies are born with severe congenital heart defects (present at birth), where the heart is unable to support two separate circulations—one to the lung and the other to the body. Such defects can occur by themselves or as part of certain genetic disorders.

Usually, hearts with congenital defects also have abnormally developed valves and holes between the heart chambers. Frequently, there is narrowing in the tubes (aorta and pulmonary artery) that carry blood out of the heart.

Each year, more than 35,000 babies in the United States are born with congenital heart defects. Single ventricle defects are one of the most severe and complicated congenital heart defects. According to the American Heart Association, congenital heart defects are the most common type of birth defect. They affect 8 out of every 1,000 newborns.

Congenital heart defects, including single ventricle defects, are the result of problems that occurred early in the heart’s development. The defect forms while your baby’s heart is developing in the womb. Like most congenital heart defects, there is no known cause for single ventricle defects.

The formation of the heart during fetal growth is a very complex process. Normally, a fetus should develop two ventricles and valves that control the blood’s entry to and exit from the heart.

Several different abnormalities in this process can result in single ventricle defects.

In some cases, the valves do not develop at all, and the blood can no longer enter or exit one of the heart’s pumping chambers. In other instances, an entire pumping chamber (ventricle) is underdeveloped and cannot pump effectively. Sometimes, the connections between different parts of the heart are highly disorganized or the orientation of the valves and heart chambers is defective, such that the heart cannot function as two distinct pumping chambers.

Any of these developmental problems ultimately can result in a single ventricle defect.

Most children with single ventricle defects show symptoms at birth or very soon afterwards. Single ventricle defects cause low oxygen levels in the blood, which can make your baby’s skin to have a bluish-purple color (cyanosis), especially around the mouth and nose.

The signs and symptoms may increase when your baby is feeding.

Other symptoms include:

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Fast breathing or breathlessness

- Poor feeding

- Lack of energy, sluggish, drowsy (lethargy)

- Weak pulse

- Pounding heart

It usually is diagnosed based on the above signs and symptoms, a physical exam, and the results from various tests and procedures.

During a physical exam, your doctor will listen to your baby’s heart and lungs to check for a murmur and will evaluate your baby’s general appearance to look for signs of a heart defect, such as a bluish tint to the skin, lips, or fingernails and rapid breathing.

Single ventricle defects are part of the critical congenital heart defects that can be detected on pulse oximetry. Pulse oximetry is a simple, non-invasive, bedside test to determine the amount of oxygen in the baby’s blood.

If the doctor suspects a single ventricle defect, your baby likely will undergo additional testing. In most cases, an echocardiogram (echo) will provide enough evidence to recommend treatment, but in rare occasions your baby may undergo a cardiac catheterization for further analysis. Additional tests that your doctor may order include a chest x-ray, electrocardiogram (EKG), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

For more information on these tests, visit our common diagnostic tests page.

Currently, no treatment can completely correct single ventricle defects and restore normal circulation.

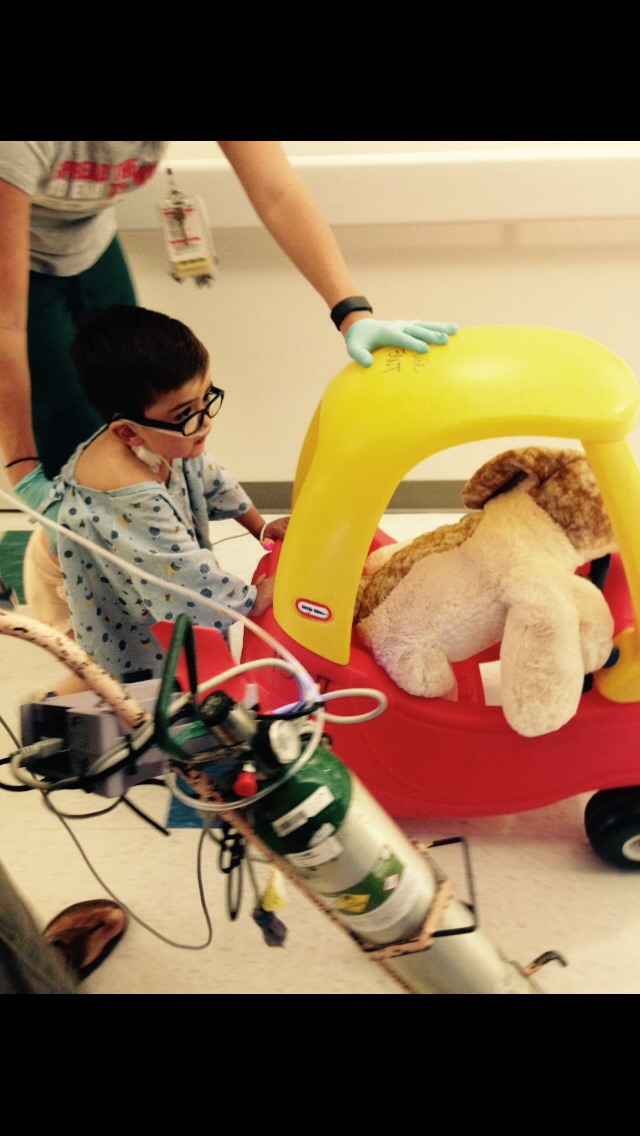

Over a series of three surgeries, a pediatric/congenital heart surgeon (cardiothoracic surgeon) will “re-route” your baby’s circulation so that oxygen-poor (blue) blood from the body will be diverted directly to the lungs for oxygenation.

This procedure allows blue blood to completely bypass the heart. Oxygen-rich (red) blood from the lungs will return to the heart and the heart will pump this blood to the rest of the body.

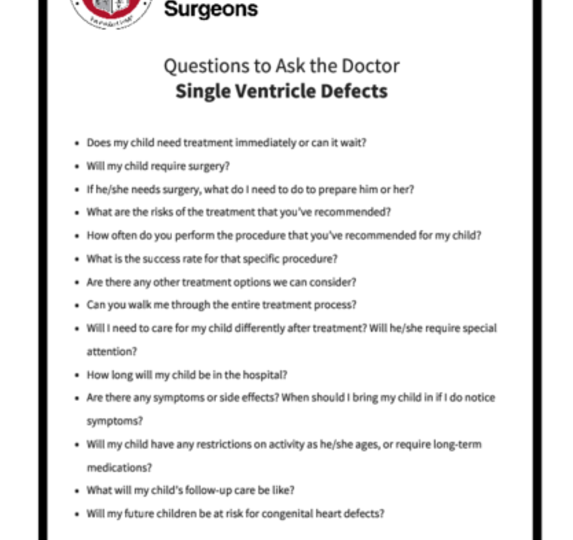

Be sure to speak with your baby’s doctor about what you should expect during and after each of the surgeries. You can print these sample questions (hyperlink to PDF of questions) to use as a basis for discussion with the doctor.

Expected outcomes: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Congenital Heart Surgery Database shows an expected outcome ranging from 6.8% mortality to 17.3% mortality, depending on the complexity of the single ventricle palliation surgery. Outcomes will vary across different programs. It is appropriate to inquire about the outcomes of a surgical group or surgeon during your consultation.

The first of these three surgeries is usually performed in the first weeks of life. During this procedure, the surgeon will ensure that there is adequate blood flow to your baby’s body and lungs, and that blood mixes freely within the heart. In some cases, this can be accomplished with a catheterization procedure performed by an interventional cardiologist. In very rare cases, the first surgery may not be required at all.

The first of these three surgeries is usually performed in the first weeks of life. During this procedure, the surgeon will ensure that there is adequate blood flow to your baby’s body and lungs, and that blood mixes freely within the heart. In some cases, this can be accomplished with a catheterization procedure performed by an interventional cardiologist. In very rare cases, the first surgery may not be required at all.

The second procedure is performed between 4 and 8 months of life. During this procedure (called Glenn or hemi-Fontan procedure), blood from your baby’s head and upper body is diverted directly to the lungs.

The second procedure is performed between 4 and 8 months of life. During this procedure (called Glenn or hemi-Fontan procedure), blood from your baby’s head and upper body is diverted directly to the lungs.

The third surgery is undertaken between 2 and 4 years of life. During this surgery (called Fontan procedure), blood from the abdomen and lower half of the body is diverted directly to the lungs. Until the third surgery is completed, the oxygen level in your child’s body will continue to be lower than normal. After the third surgery, most children will have normal oxygen levels in their blood.

The third surgery is undertaken between 2 and 4 years of life. During this surgery (called Fontan procedure), blood from the abdomen and lower half of the body is diverted directly to the lungs. Until the third surgery is completed, the oxygen level in your child’s body will continue to be lower than normal. After the third surgery, most children will have normal oxygen levels in their blood.

Successful management of single ventricle defects has been possible only over the past few decades and doctors continue to follow these children to better understand the long-term outcomes. With improvements in management, children with single ventricle defects are able to live longer and more meaningful lives.

Even after your child has recovered fully from the surgery, he or she will require lifelong follow-up care with a heart specialist and will need to be on medications in the long-term.

Your child also will be required to take antibiotics during dental procedures to prevent infections that may cause inflammation of the heart (endocarditis).

Long-term outcomes in children with single ventricle defects depend on factors, such as the exact nature of the heart defect and associated genetic or non-cardiac abnormality, if any. Some of these children can have relatively normal development and successfully be able to complete school and college. They may be able to participate in recreational sports. A few children with single ventricle defects have reached adulthood and have had children of their own.

Some children with single ventricle defects will require additional procedures as they grow.

These may include additional surgeries on the heart valves, to open up narrowing in the surgical connections or to address electrical rhythm abnormalities of the heart. Alternatively, they can require catheterizations and interventions to improve the functioning of the heart. In a subset of children with single ventricle defects, the heart function continues to deteriorate over time, and they may ultimately require a heart transplant.

Reviewed by: Lauren Kane, MD

December 2017