- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

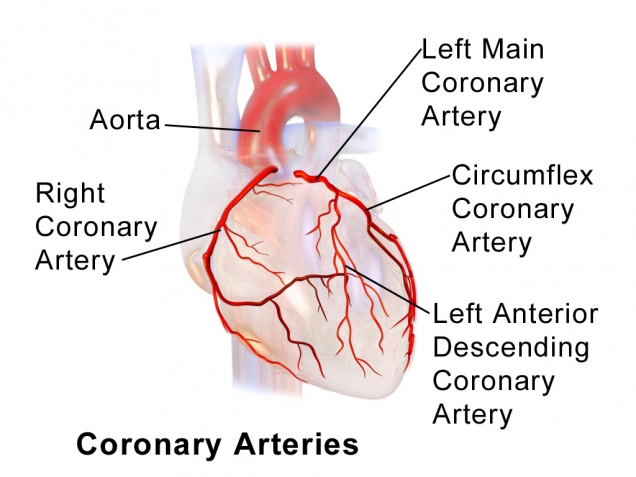

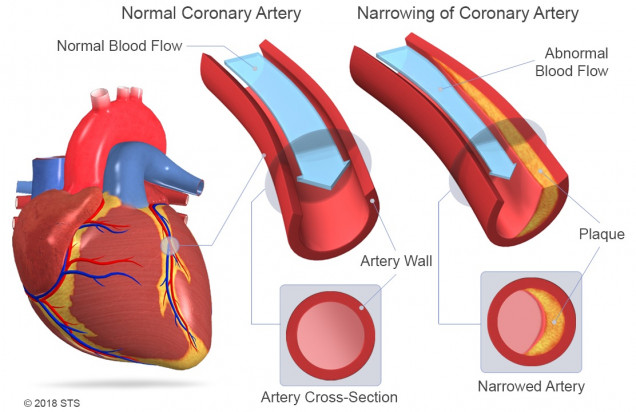

The coronary arteries carry blood to the heart, supplying it with the oxygen and nutrients that the heart muscle needs to function. There are two major arteries that branch off of the aorta to supply blood to the heart. They are called the right coronary artery and the left main coronary artery.

The right coronary artery provides blood flow to the right side of the heart. The left main coronary artery divides into the left anterior descending artery, which supplies blood to the front of the left side of the heart, and the circumflex artery which supplies blood to the left side and back of the heart.

When people talk about coronary artery disease or coronary heart disease, they are usually referring to partial or total blockages of the coronary arteries. This is the most common form of heart disease, and occurs when cholesterol and fatty deposits (called plaques) build up over time on the inner walls of the coronary arteries. These plaques decrease blood flow to the heart by partially or completely blocking blood flow to the area of the heart supplied by the diseased artery or arteries.

When plaque decreases blood flow to your heart, your heart doesn’t receive the oxygen and vital nutrients it needs to work properly. This is known as cardiac ischemia, and causes chest pain or chest pressure known as angina. When blood flow through a coronary artery becomes severely restricted or a coronary artery becomes suddenly blocked, the heart muscle that it supplies can die. This is referred to as a heart attack or myocardial infarction. That affected portion of the heart muscle turns to scar and is no longer able to contribute to heart function.

Because coronary artery disease often develops over decades, it can go unnoticed until you have a heart attack.

Risk factors for coronary artery disease include:

- High blood pressure

- High LDL (bad) cholesterol

- Low HDL (good) cholesterol

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- Obesity

-

Unhealthy diet (high in saturated or trans fats)

Other risk factors may include sleep apnea, high stress levels, heavy alcohol intake, and preeclampsia.

Having a sedentary lifestyle (limited activity or exercise) can increase your risk of developing coronary artery disease because it often leads to some of the conditions listed above.

Your risk for heart disease also grows as you age due to genetic (things that run in your family) or lifestyle factors that cause plaque to build up in your arteries.

If your father or a brother was diagnosed with heart disease before age 55, or if your mother or a sister was diagnosed before age 65, you have a greater risk of being diagnosed with heart disease.

By the time you reach middle age, enough plaque may have built up to begin causing warning signs or symptoms. Although older age and a family history of early heart disease are risk factors, you can reduce your own chances of developing the disease by controlling other risk factors, such as your weight, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels.

If you are worried that you may be at risk for heart disease, be sure to talk with your doctor about ways to reduce your risk. And talk to your doctor before starting any exercise program to decide what is right for you.

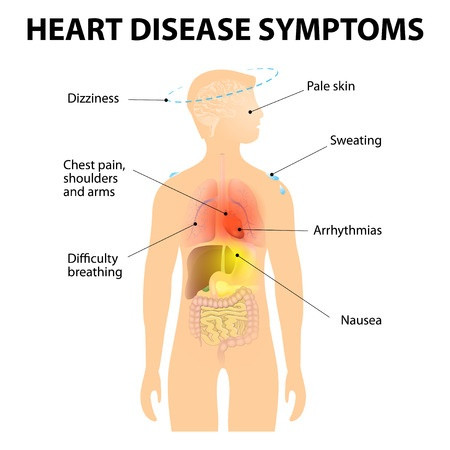

If your coronary arteries narrow, they can’t supply enough blood to your heart, especially when it’s beating hard, such as during exercise. At first, the decreased blood flow may not cause symptoms, but as plaque continues to build in your coronary arteries, your heart muscle doesn’t get the blood it needs and symptoms may develop. Symptoms may develop gradually (chronic) or suddenly (unstable angina or heart attack).

Copyright: designua/123RF Stock Photo

The most common symptoms of coronary artery disease include chest pain (angina) and shortness of breath with some kind of exercise or exertion. Though you may not have symptoms at rest, more strenuous activity increases the amount of oxygen that the heart needs, and brings on symptoms. Chest pain can also be described as discomfort, heaviness, tightness, pressure, aching, burning, numbness, fullness, or squeezing. It can be mistaken for indigestion or heartburn and can occur anywhere in the chest, and sometimes even the abdomen. The severity of these symptoms varies, and they may get more severe as plaque continues to build up and narrow your coronary arteries. Lack of energy and inordinate fatigue with the same level of activity may also be a sign of heart disease.

If left untreated, coronary artery disease can lead to a heart attack.

Common symptoms of heart attack include chest pain or discomfort that lasts more than a few minutes and doesn’t go away with rest. There may be upper body discomfort, and shortness of breath. Other possible symptoms of a heart attack include breaking out in a cold sweat, feeling unusually tired for no reason, nausea (sick to your stomach) and vomiting, and light-headedness or sudden dizziness. Associated symptoms such as pain the arms, neck, jaw, or upper stomach can also be surrogates for chest pain.

If you experience any of these symptoms, seek immediate treatment. Do not wait to schedule an appointment with your doctor; call 9-1-1 or have someone drive you to the emergency room to get checked out immediately.

Your doctor usually can diagnose coronary artery disease based on your medical history, risk factors, a physical exam, and the results from tests and procedures.

There is no one test that can diagnose coronary artery disease, so your doctor may recommend one or more of the following: electrocardiogram (EKG), stress test, echocardiogram (echo), chest x-ray, blood tests, and cardiac catheterization (angiogram). For more information on these tests, visit the common diagnostic tests page.

Many patients with coronary artery disease can be treated with medications alone. The most common procedures to treat coronary artery disease include coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Both treatment options will restore blood flow to your heart, but there is no one treatment guaranteed to be effective for all cases of coronary artery disease. In general, both CABG and PCI are designed to make patients with coronary artery disease live longer by decreasing the likelihood of dying from a heart attack (myocardial infarction). These procedures are also very effective at improving the symptoms of coronary artery disease, including chest pain and shortness of breath.

Who gets Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Surgery (CABG) vs. Catheter Based Therapy (PCI) vs. Medications only?

Extensive research and over 50 years of experience with CABG and 30 years of experience with PCI have helped to determine which patients do better with CABG and which are better candidates for PCI. The decision can be complicated and depends on the number and location of blockages in the coronary arteries, the condition of the patient, the function of the heart, and the presence of contributing diseases such as diabetes. Your cardiologist and cardiac surgeon will work together to decide which procedure is the best for you. Though CABG is more invasive than PCI, most patients with blockage of the left main coronary artery, blockages in all three of the major coronary arteries, those with weaker ventricles, and diabetics with severe coronary artery disease do better long term with CABG. Some patients do not need either CABG or PCI, and can be treated with medications alone.

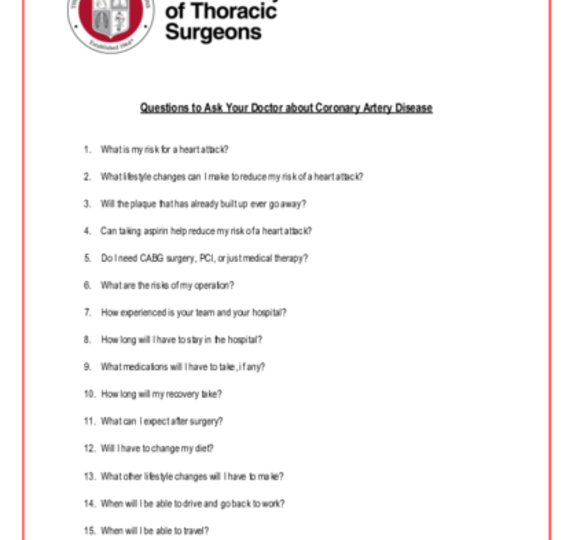

Talk with your doctor or cardiothoracic surgeon to get more information on these treatment options and choose the one that is best for you. You can print these sample questions to use as a basis for discussion with your doctor.

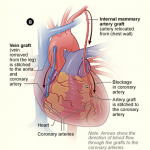

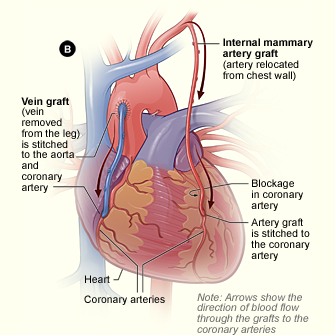

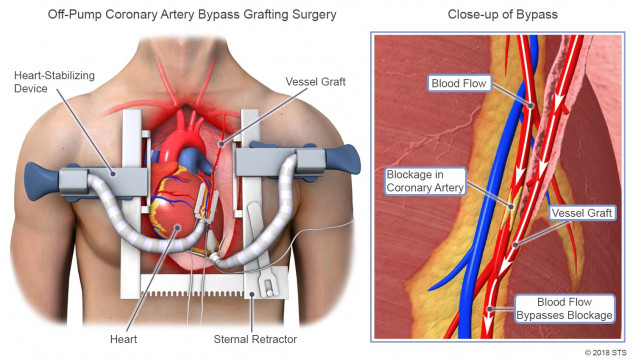

CABG (often pronounced “cabbage”) is the most commonly performed heart operation in the United States. The operation is designed to bypass the blockages in your coronary arteries in order to restore normal or near normal blood flow to the entire heart during rest and exercise. Though an occasional patient needs only one bypass graft, most people who are candidates for CABG have blockages in most of their coronary arteries and need between three and five bypass grafts.

Your surgeon will take a healthy blood vessel (artery or vein from your body), usually from your leg, arm, chest or abdomen, and connect it to the other arteries (usually the aorta) in your heart. This enables blood flow to “bypass,” or go around, the diseased or blocked portion of your coronary artery, creating a new path for blood flow to your heart.

Coronary bypass surgery typically takes between three and five hours to perform. To begin the CABG operation, a cardiac surgeon will make an incision down the front of your chest, usually dividing your breastbone or sternum. This incision is called a median sternotomy, and it enables the surgeon to safely operate on all parts of your heart. The size of the actual incision varies from surgeon to surgeon. Ask your surgeon about the details of your incision and what to expect after your operation.

During the surgery, you typically will be connected to a heart-lung machine (sometimes called “the pump”), which is a machine that temporarily takes over the function of your heart and lungs during surgery to maintain blood circulation and oxygen flow through your body. However, some surgeons perform to perform CABG operations without the use of the heart-lung machine. The heart-lung machine allows the surgeon to stop your heart in order to carefully and accurately sew your bypass grafts to your heart. The average coronary artery is about 2-3 millimeters in diameter, which is the width of a typical blade of grass. After the surgery is completed, you will be taken off the pump, and your heart and lungs will resume their function. After CABG, most patients spend one night in an intensive care unit, followed by another 3 to 5 days in the hospital.

“Off-pump” vs. “On Pump” CABG

Some surgeons prefer to perform CABG without the use of the heart lung machine (“off pump”) by sewing the coronary bypass grafts to the coronary arteries with the heart beating. This technique requires the use of instruments that “stabilize” or hold the area of the coronary artery being bypassed still so that the surgeon can carefully and accurately sew the graft to it.

Off-pump or beating heart CABG was developed in an attempt to decrease the chances of complications after surgery, including bleeding, stroke, lung problems, and kidney toxicity. It may also be more economical to perform because it eliminates the costs of the heart lung machine. Off-pump CABG has been proven to be safe and effective in the hands of many surgeons. Whether or not it actually decreases the risk of conventional CABG while still offering the excellent long term results of on-pump CABG is still a matter of debate among cardiac surgeons. Ask your cardiac surgeon which method he prefers and why.

Risks of CABG

CABG has been proven to be safe and effective, but like all procedures on the heart, it can result in serious complications. The chance of a major complication occurring depends on your age and condition going into the operation. Though CABG can be performed safely in patients in their late eighties and even early nineties, the risk increases with age. It also increases with preexisting conditions, such as a previous stroke, heart attack, kidney disease, lung problems, or other conditions that weaken the body or prevent your ability to recover after the operation. The overall death rate after CABG is less than 3 percent. There is also a small but real risk of stroke, heart attack, bleeding, kidney failure, pneumonia, and wound infection. Many patients require blood transfusions during or after their operations. Though no one has a crystal ball, your surgeon is an expert at evaluating your potential to do well with CABG, and at determining and discussing your risks with you.

You can access the STS Risk Calculator, which can help calculate your risk of death or other complications from certain types of heart surgery. The results can help you and your doctor to determine the best course of treatment. The STS National Database has collected information from millions of patients in order to predict risk and assure quality associated with CABG.

CABG (often pronounced “cabbage”) is the most commonly performed heart operation in the United States. The operation is designed to bypass the blockages in your coronary arteries in order to restore normal or near normal blood flow to the entire heart during rest and exercise. Though an occasional patient needs only one bypass graft, most people who are candidates for CABG have blockages in most of their coronary arteries and need between three and five bypass grafts.

Your surgeon will take a healthy blood vessel (artery or vein from your body), usually from your leg, arm, chest or abdomen, and connect it to the other arteries (usually the aorta) in your heart. This enables blood flow to “bypass,” or go around, the diseased or blocked portion of your coronary artery, creating a new path for blood flow to your heart.

Coronary bypass surgery typically takes between three and five hours to perform. To begin the CABG operation, a cardiac surgeon will make an incision down the front of your chest, usually dividing your breastbone or sternum. This incision is called a median sternotomy, and it enables the surgeon to safely operate on all parts of your heart. The size of the actual incision varies from surgeon to surgeon. Ask your surgeon about the details of your incision and what to expect after your operation.

During the surgery, you typically will be connected to a heart-lung machine (sometimes called “the pump”), which is a machine that temporarily takes over the function of your heart and lungs during surgery to maintain blood circulation and oxygen flow through your body. However, some surgeons perform to perform CABG operations without the use of the heart-lung machine. The heart-lung machine allows the surgeon to stop your heart in order to carefully and accurately sew your bypass grafts to your heart. The average coronary artery is about 2-3 millimeters in diameter, which is the width of a typical blade of grass. After the surgery is completed, you will be taken off the pump, and your heart and lungs will resume their function. After CABG, most patients spend one night in an intensive care unit, followed by another 3 to 5 days in the hospital.

“Off-pump” vs. “On Pump” CABG

Some surgeons prefer to perform CABG without the use of the heart lung machine (“off pump”) by sewing the coronary bypass grafts to the coronary arteries with the heart beating. This technique requires the use of instruments that “stabilize” or hold the area of the coronary artery being bypassed still so that the surgeon can carefully and accurately sew the graft to it.

Off-pump or beating heart CABG was developed in an attempt to decrease the chances of complications after surgery, including bleeding, stroke, lung problems, and kidney toxicity. It may also be more economical to perform because it eliminates the costs of the heart lung machine. Off-pump CABG has been proven to be safe and effective in the hands of many surgeons. Whether or not it actually decreases the risk of conventional CABG while still offering the excellent long term results of on-pump CABG is still a matter of debate among cardiac surgeons. Ask your cardiac surgeon which method he prefers and why.

Risks of CABG

CABG has been proven to be safe and effective, but like all procedures on the heart, it can result in serious complications. The chance of a major complication occurring depends on your age and condition going into the operation. Though CABG can be performed safely in patients in their late eighties and even early nineties, the risk increases with age. It also increases with preexisting conditions, such as a previous stroke, heart attack, kidney disease, lung problems, or other conditions that weaken the body or prevent your ability to recover after the operation. The overall death rate after CABG is less than 3 percent. There is also a small but real risk of stroke, heart attack, bleeding, kidney failure, pneumonia, and wound infection. Many patients require blood transfusions during or after their operations. Though no one has a crystal ball, your surgeon is an expert at evaluating your potential to do well with CABG, and at determining and discussing your risks with you.

You can access the STS Risk Calculator, which can help calculate your risk of death or other complications from certain types of heart surgery. The results can help you and your doctor to determine the best course of treatment. The STS National Database has collected information from millions of patients in order to predict risk and assure quality associated with CABG.

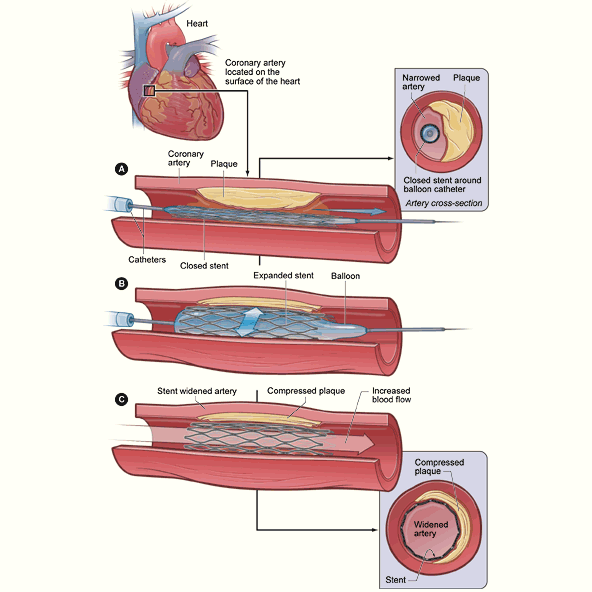

PCI, sometimes referred to as angioplasty, is a nonsurgical procedure that can open blocked or narrowed coronary arteries. A thin, flexible tube with a balloon or other device attached to the end will be threaded through one of your blood vessels up to the affected artery. Once in place, the balloon is inflated to create a larger opening and restore blood flow through the artery. During the procedure, you may also have a small mesh tube, called a stent, placed into your artery. The stent helps prevent further blockages. Because PCI is much less invasive than CABG and does not require an incision in the chest, the recovery period is much quicker. PCI, performed by an interventional cardiologist and not a cardiac surgeon, is usually limited to patients who have blockages in fewer coronary arteries than CABG patients.

You may also be able to manage your coronary artery disease through lifestyle changes and medications. A conversation with your doctor can help you decide what treatment is best.

PCI, sometimes referred to as angioplasty, is a nonsurgical procedure that can open blocked or narrowed coronary arteries. A thin, flexible tube with a balloon or other device attached to the end will be threaded through one of your blood vessels up to the affected artery. Once in place, the balloon is inflated to create a larger opening and restore blood flow through the artery. During the procedure, you may also have a small mesh tube, called a stent, placed into your artery. The stent helps prevent further blockages. Because PCI is much less invasive than CABG and does not require an incision in the chest, the recovery period is much quicker. PCI, performed by an interventional cardiologist and not a cardiac surgeon, is usually limited to patients who have blockages in fewer coronary arteries than CABG patients.

You may also be able to manage your coronary artery disease through lifestyle changes and medications. A conversation with your doctor can help you decide what treatment is best.

As part of your recovery and to reduce the risk of developing further blockages, you should strive to maintain a healthy lifestyle. This includes regular exercise, eating healthy foods, weight loss, reducing stress, and quitting smoking. Even if you do not require surgery or PCI, incorporating healthy behaviors will help prevent further damage to your heart.

CABG surgery is a major operation, and you should expect to be in the hospital for about a week after surgery. Your hospital stay will likely include a day or two in the intensive care unit (ICU) where hospital staff can monitor your blood pressure, breathing, and other vital signs. You also will have a breathing tube for a few hours or possibly overnight, so communication will be difficult. The breathing tube will be removed as soon as you are awake and able to breathe on your own.

If your in-hospital recovery goes as expected, you should be discharged within a week. This is just the start of your recovery though. Even after going home, you likely will find it difficult to perform everyday tasks or even walk a short distance. You should expect a full recovery period of about 12 to 15 weeks. In most cases, you can return to work, begin exercising, and resume sexual activity after 4 to 6 weeks, but your doctor will discuss a personalized recovery plan with you following surgery.

Reviewed by: V. Seenu Reddy, MD, MBA, and Kendra J. Grubb, MD, MHA

April 2018