- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

ASDs account for between 5% and 10% of all cases of congenital heart disease and are twice as prevalent among girls as boys. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that nearly 2,000 babies in the United States are born with an ASD each year.

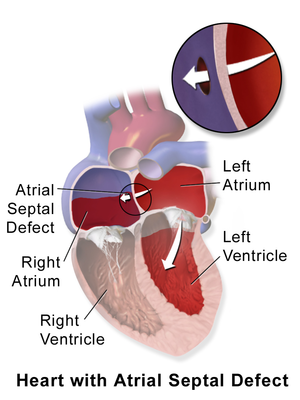

As a fetus develops, there can be several openings in the atrial septum, but they usually close before or shortly after birth. The holes can vary in size, and if they do not close on their own, they may need to be surgically repaired.

There are three main types of ASDs:

- Secundum: The most common type of ASD; the hole is located in the middle of the septum

- Primum: The hole is in the lower part of the atrial septum and may occur with other congenital heart defects

- Sinus Venosus: Rare; the hole is near the veins bringing blood back to the heart from the lungs and often occurs with other congenital heart defects

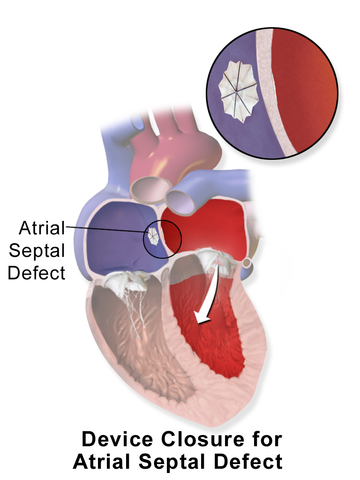

When your child’s heart is affected by an ASD, blood flows through the hole primarily from the left atrium to the right atrium. This causes increased blood flow through the lungs, which can lead to enlargement of the right side of the heart.

Congenital heart defects, such as ASDs, are the result of problems that occurred early in the heart’s development.

Often, there is no direct cause but it is thought that genetics and environmental factors may play a role.

ASDs vary in size and in the severity of symptoms they may cause.

In most children, ASDs cause no symptoms.

If the defect is large enough, however, the volume of blood flowing through it can cause shortness of breath, fatigue, or poor growth, but these symptoms are uncommon.

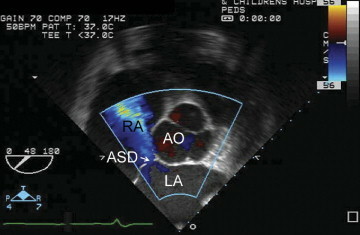

Most often, the physician will hear a heart murmur during your child’s exam and order additional testing, such as an echocardiogram (echo).

As a first step, your child likely will undergo a chest x-ray, which may show enlargement of the heart and increased blood flow to the lungs. Your doctor may also use an electrocardiogram (EKG) to diagnose an ASD. For more information on these tests, visit our common diagnostic tests page.

In some children, an ASD may close on its own without any treatment. With a small ASD, the rate of spontaneous closure may be as high as 80% in the first 18 months of life.

If your child’s ASD is still present by age 3 years, it likely will never close on its own and will require surgery.

If left untreated, ASDs can cause severe problems in adulthood including:

- Pulmonary hypertension – High blood pressure in the lungs that, in rare cases, can cause permanent damage called Eisenmenger syndrome

- Congestive heart failure – Weakening of the heart muscle

- Atrial arrhythmias – Abnormal rhythms or beating of the heart

- Increased risk of stroke

If your child’s ASD requires closure, there are generally two options: open heart surgery and transcatheter device closure. Open heart surgery is performed by a cardiothoracic surgeon, while transcatheter device closure is typically performed by an interventional cardiologist.

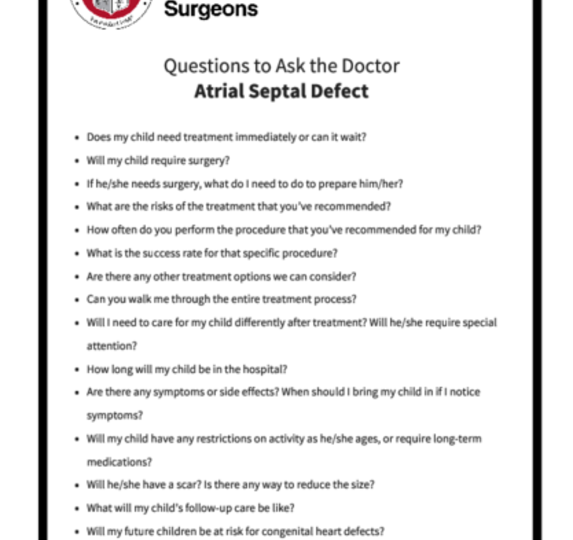

Be sure to speak with your doctor about what procedure is right for your child. You can print these sample questions to use as a basis for discussion with your doctor.

Expected outcomes: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Congenital Heart Surgery Database shows an expected outcome of <1% mortality for isolated atrial septal defect. Outcomes will vary across different programs. It is appropriate to inquire about the outcomes of a surgical group or surgeon during your consultation.

During open heart surgery, your child is placed on a heart-lung bypass machine. This machine takes over the function of the heart and lungs to provide oxygenated blood to the body.

The cardiothoracic surgeon may be able to close the hole with stitches (sutures) or with a patch. Overall, surgery is very effective and is fairly low risk for your child.

During open heart surgery, your child is placed on a heart-lung bypass machine. This machine takes over the function of the heart and lungs to provide oxygenated blood to the body.

The cardiothoracic surgeon may be able to close the hole with stitches (sutures) or with a patch. Overall, surgery is very effective and is fairly low risk for your child.

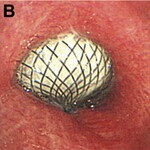

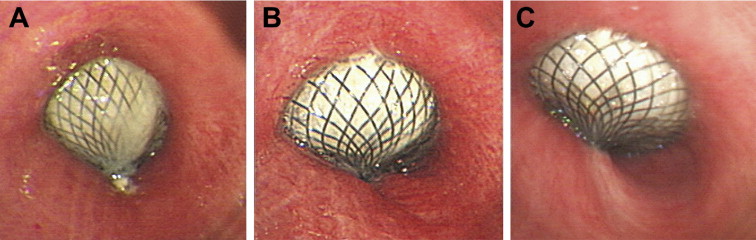

Depending on the size and the area of the septum involved, your child may be eligible for transcatheter device closure which is usually performed by an interventional cardiologist. This procedure closes an ASD using a device that is inserted through a catheter. The catheter is a long thin tube, about the diameter of a piece of spaghetti, which is directed to the heart through the large blood vessels in the leg.

The benefits of being able to close an ASD with a transcatheter device is that the procedure can be performed without stopping your child's heart or requiring the heart-lung bypass machine.

Depending on the size and the area of the septum involved, your child may be eligible for transcatheter device closure which is usually performed by an interventional cardiologist. This procedure closes an ASD using a device that is inserted through a catheter. The catheter is a long thin tube, about the diameter of a piece of spaghetti, which is directed to the heart through the large blood vessels in the leg.

The benefits of being able to close an ASD with a transcatheter device is that the procedure can be performed without stopping your child's heart or requiring the heart-lung bypass machine.

Sometimes, an ASD can go unnoticed until your child reaches adulthood because a small ASD may have no significant effect on your child’s health. As an adult, if the ASD is big enough to cause enlargement of the right heart chambers, surgical repair may be recommended to protect the heart from physical deterioration.

Sometimes, an ASD can go unnoticed until your child reaches adulthood because a small ASD may have no significant effect on your child’s health. As an adult, if the ASD is big enough to cause enlargement of the right heart chambers, surgical repair may be recommended to protect the heart from physical deterioration.

Surgical repair is fairly safe and complications are rare.

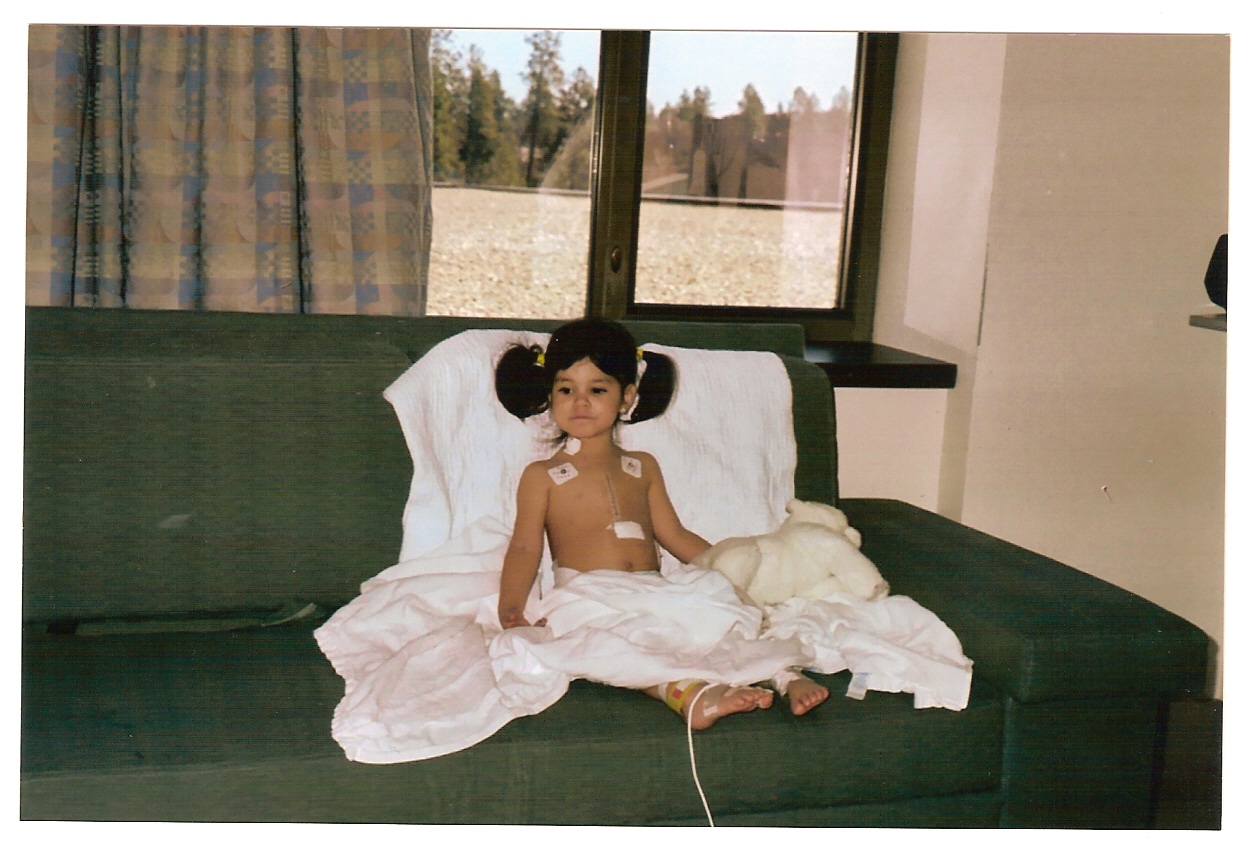

Following surgery, your child may have to remain in the hospital for 2 to 5 days for routine monitoring and follow-up. Your child also likely will have just a short stay in the intensive care unit (ICU).

If an ASD is surgically closed in childhood, the heart slowly returns to a normal size, usually in 4 to 6 months. Your child should not experience any physical problems and should have no restrictions or limitations on physical activity.

As with any heart surgery, your child will have to see a pediatric heart specialist for regular checkups, but additional surgery is rarely required. If your child underwent transcatheter device closure, your doctor likely will recommend closer follow-up to monitor for complications with the device.

Many patients have normal heart rhythm following the operation, but there is a chance that your child will continue to have signs of rhythm problems, which may require ongoing monitoring and treatment.

Once your child reaches adulthood, he or she will need periodic evaluation, depending on his or her own personal circumstances. An echo may be ordered every 5 years or so to look for complications from the repair.

Reviewed by: Ram Kumar Subramanyan, MD, PhD

December 2017