- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

August 23, 2019

Underneath the seemingly simple question, “Should I be screened for lung cancer?,” lies a contentious debate.

For many lung cancer patients and advocates, the answer would seem to be an easy and resounding “Yes!” After all, lung cancer is by far the most common cancer killer. It claims more lives than breast, colon, and prostate cancers combined, all of which have readily available screening tests. Unlike patients with those cancers, most lung cancer patients are diagnosed with stage IV, metastatic disease, a clear demonstration of the strong need for earlier detection.

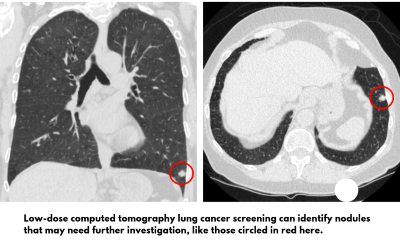

The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) showed in 2011 that using low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) to screen patients with a significant smoking history resulted in a 20% reduction in lung cancer deaths, compared to screening with chest x-rays (CXR).

Lung cancer screening would therefore seem to be a “no-brainer,” backed by strong clinical research and carefully considered government recommendations.

Why then do lung cancer screening rates of eligible patients still hover at less than 10%, and why do many physicians still balk at the idea of sending their patients for LDCT screening?

The answers to those questions are complex because some reactions are based on misunderstandings, while others are based on fears.

100,000 Lives Could Be Saved

Some confusion may exist because the 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality is a relative, rather than absolute, reduction. The actual numerical comparison was 1.33% versus 1.66% for the LDCT and CXR groups, respectively, in the NLST, which sounds noticeably less exciting than the relative reduction of 20%. However, the potential societal benefits when applied to the entire at-risk population are huge.

Researchers have estimated that if lung cancer screening rates approached 75% of eligible patients (comparable to rates of breast and cervical cancer screenings), more than 100,000 lung cancer deaths could be avoided by 2030.

Chance of Overdiagnosis, False Positives Reduced

The initial NLST study estimated that 18.5% of lung cancers detected by LDCT were “overdiagnosed” after 6.4 years of follow-up. In other words, these cancers were so slow-growing that they would not have required treatment. However, that didn’t mean that these lesions wouldn’t become cancerous in the future; previous studies have estimated that it takes at least 10 years before a lung adenocarcinoma becomes symptomatic.

To help reduce the chance of and allay fears about overdiagnosis, a new lung imaging reporting and data system (Lung-RADS) is now available. Lung-RADS is similar to reporting systems used for mammography. It standardizes recommendations and diminishes confusion in image interpretations.

Lung-RADS also may help reduce the rate of false positives. That’s when nodules, which have an exceedingly low chance of developing into cancer, are investigated with invasive biopsy procedures and later shown to be benign. The good news, however, is that patients enrolled in the NLST who were found to have lung nodules or incidental findings did not report more anxiety or a worse quality of life than patients whose screening exams were negative.

Screening Is Not Harmful

Major complications occurred in only 0.06% of NLST patients with positive LDCT screening studies but who did not ultimately have cancer.

In my opinion, the harms of LDCT screening have been sensationalized by those who oppose screening. It is remarkable that opinion pieces written by prominent authors could rigorously challenge the survival benefit and statistical methodology of a large, randomized, well-powered study such as the NLST, and then have no hesitation quoting “harms” not directly ascribed to or powered for in the screening study as definitive fact. This results in misleading patient handouts and charts in which the harms appear to outweigh or be almost equal to the number of lives saved. Such information ignores the fact that the vast majority of complications occurred in patients subsequently found to have lung cancer—complications that resulted from the treatment of the cancer, not the screening itself.

Lung Cancer Is Treatable

Survival rates for early stage cancer continue to rise and even subsets of patients diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer can expect to live for years after their diagnosis with targeted therapies or immunotherapy.

It is certainly important for patients to understand the benefits and downsides of screening, but they also should be informed about those concepts by medical professionals who are themselves informed and unbiased.

An incredible opportunity exists to change the death toll and the burden to patients and society resulting from diagnoses of late-stage lung cancer. Without a doubt, lung cancer screening facilitates early diagnosis and saves lives.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons.