- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

October 10, 2018

We hear a lot nowadays about genetics in popular culture, from discovering your ancestry, to learning about your risk for Alzheimer’s disease, to finding out if you have a genetic predisposition for cancer.

What is less talked about, but is certainly an area of growing interest, is how cardiovascular disease may be explained by your DNA.

DNA, or genetic material, is like a set of instructions for our bodies. Our trillions of cells hold the DNA, which tells our bodies how to develop, grow, and function. DNA also is what we pass on to our children. Though it’s sometimes hard to believe, half of your DNA comes from your mom and half comes from your dad.

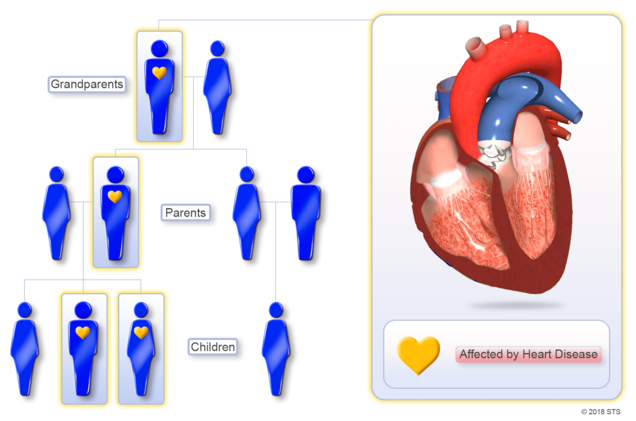

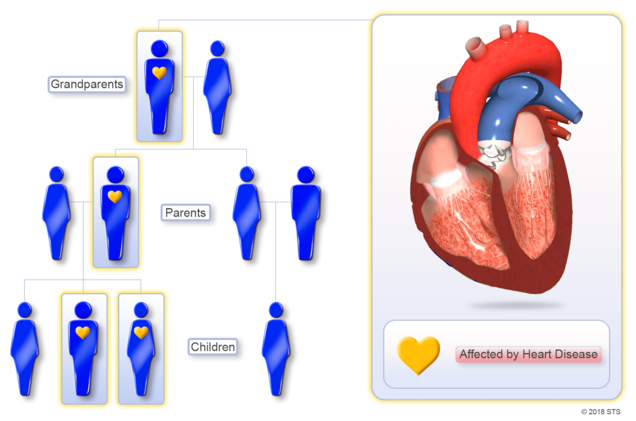

No sets of DNA are the same (unless you are identical twins), and we all have variations that make us unique. The variations in our DNA determine things like hair color, height, and face shape, but sometimes DNA variations can cause disease. This can be the case for some cardiovascular diseases, including aortic aneurysms, bicuspid aortic valves (when the valve has two cusps—also called leaflets—instead of three), and coronary artery disease.

Image

Aortic aneurysms

The aorta is the main blood vessel exiting the heart and carries blood to the rest of the body. An aortic aneurysm is when there is a bulge or enlargement in part of the aorta, causing the tissue to become weaker and susceptible to tearing or rupture.

Aortic aneurysms are more common with older age, or when people have had uncontrolled high blood pressure for many years. In other words, an aneurysm can be a part of normal wear and tear. However, there are certain signs pointing to a genetic cause.

An aortic aneurysm is more likely to be genetic when:

- It occurs before age 50-60, especially without high blood pressure.

- Family members also have had aortic aneurysms.

- Along with aneurysm, there are eye, joint, or bone problems (things like lens dislocation, really flexible joints, or scoliosis). These are signs of Marfan syndrome.

Bicuspid aortic valve

The aortic valve helps control blood flow through the left side of the heart and out the aorta. Normally, it is tricuspid, meaning there are three leaflets that open and close together. In about 1%-2% of the population, the valve is bicuspid (it has only two leaflets). Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is the most common birth defect of the heart. BAV can become dangerous over time, causing problems with blood flow and aortic aneurysms.

BAV has genetic causes and tends to run in families. When one person has BAV, there is a 30% chance that at least one close relative also has it. As a result, it is recommended that first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, and children) get an echocardiogram to check if they also have BAV. Early detection helps prevent problems down the line.

Coronary artery disease

Otherwise known as “clogged arteries,” coronary artery disease (CAD) is when the blood vessels feeding the heart become blocked, leading to heart attack and heart dysfunction. CAD is the most common type of heart disease and is the leading cause of death in the United States. In most cases, lifestyle choices, such as what we eat, smoking, alcohol, and stress, contribute to CAD. But have you ever wondered why two people can live similar lifestyles with high risk factors and one has heart problems while the other doesn’t? Or why some people who live the healthiest lifestyles somehow still have heart attacks? We usually can explain this by genetics.

The most obvious example of genetic predisposition to CAD is something called familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). Basically, FH is really high cholesterol from childhood that is not caused by lifestyle factors, but by our genes. FH is common, affecting approximately 1 in every 250 people.

So what are the clues that you may have FH?

- LDL cholesterol is high (>190 mg/dL) without cholesterol lowering medication.

- Family members have had heart attacks at a young age.

What to do?

If you think there may be a genetic cause to your cardiovascular disease, it is important to talk to a genetic specialist, such as a genetic counselor like me.

Genetic specialists will go through your personal and family history to see if there could be genetic disease running in your family. They may do genetic testing (usually a saliva sample). We swear, it’s not scary! Based on your results, we may recommend additional workup or make changes to optimize your management.

And don’t forget about the family! These genetic specialists also will tell you who in the family is at risk and give recommendations for what they should do. After all, we’re sure our goals are similar to yours—to help you and your family be the healthiest possible.

You can speak to your doctor about local genetic specialists, or go to: https://www.nsgc.org/findageneticcounselor to find a genetic counselor in your area.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons.