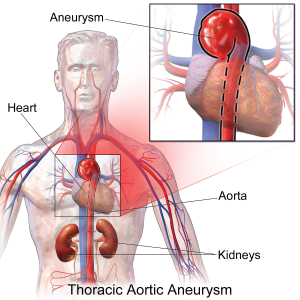

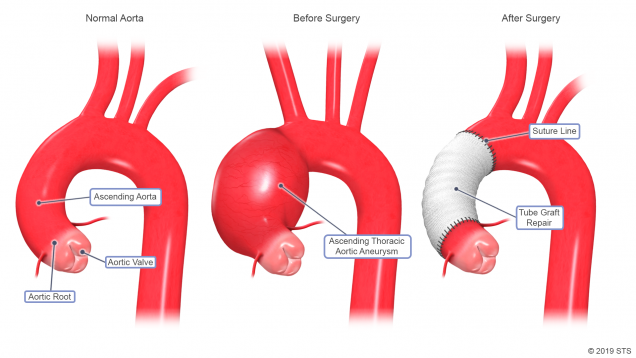

An aneurysm is a weakening in the wall of an artery, which causes it to “balloon” or expand in size. Although an aneurysm can develop anywhere along your aorta, most occur in the section running through your abdomen (abdominal aneurysms). Others occur in the section that runs through your chest (thoracic aneurysms) and above the diaphragm.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, aortic aneurysms were reported as the primary cause of 9,863 deaths in the US in 2014, but the actual number is likely much higher.

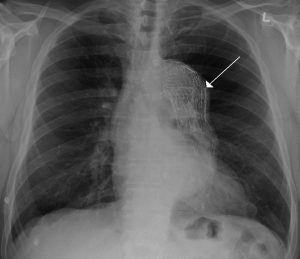

Aneurysms are often found incidentally during evaluation of other problems. Since they commonly cause no pain or discomfort, aneurysms can silently enlarge for long periods of time without being identified. When the aneurysm gets too large, it can cause pressure on a neighboring organ, or the wall of the blood vessel can split or tear (aortic dissection/dissecting aortic aneurysm) or even “burst” under the pressure (aortic rupture/ruptured aortic aneurysm).