- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

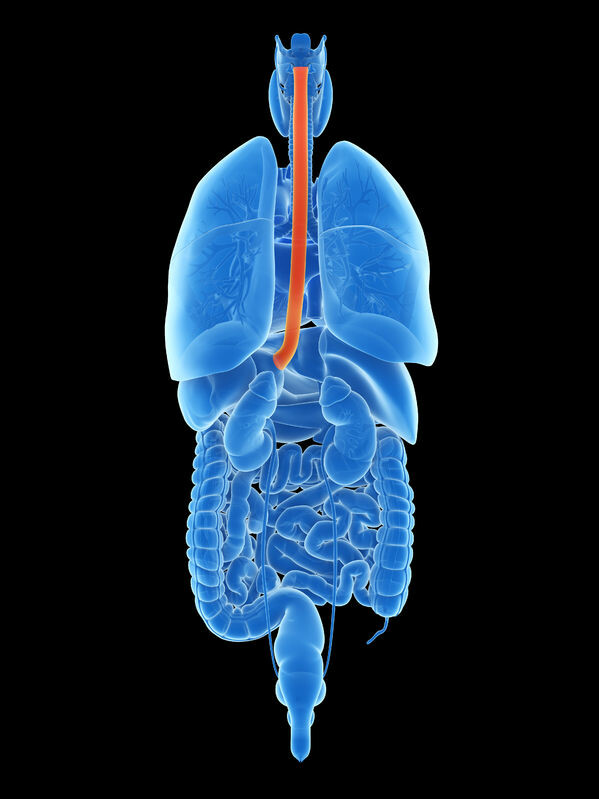

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

In some people, the muscles of the esophagus don’t work properly so the contents of their stomach flow backward into their esophagus on a regular basis (chronic acid reflux). Barrett's esophagus can occur when the reflux continually damages the lining of your esophagus.

No one knows how many people have Barrett’s esophagus, but it is estimated to affect one in every 15 people. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases reports that Barrett’s esophagus occurs twice as often in men than in women and more often among Caucasians than any other race.

Many doctors agree that the main cause of Barrett’s esophagus is recurring reflux of acid or other stomach contents into the esophagus, which damages the esophageal lining.

It is also thought that some people are predisposed to developing Barrett’s esophagus based on their genetic makeup.

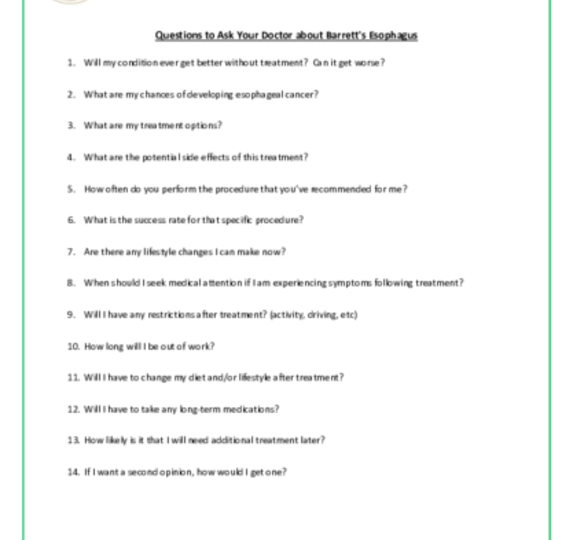

Drawing of a microscopic piece of the esophagus showing the abnormal tissue of Barrett’s esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus usually does not cause any signs or symptoms, but there is a strong relationship to long-term gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Symptoms of Barrett’s esophagus may be similar to those of GERD:

- A burning sensation in the chest (heartburn)

- Backing up of stomach acids (reflux) with a sour or bitter taste in your mouth

- Stomach discomfort (dyspepsia) with nausea or bloating after eating

See more information on gastroesophageal reflux disease

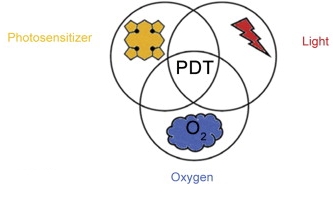

If you have a history of heartburn or acid reflux or have been diagnosed with GERD, ask your doctor about your risk of developing Barrett’s esophagus. You can print these sample questions to use as a basis for discussion with your doctor.

The only way to diagnose Barrett’s esophagus is with an upper endoscopy and biopsy. During an endoscopy a long flexible tube with a camera is placed through your mouth into your esophagus. You will be given a sedative before the procedure, so it may feel uncomfortable but will not be painful.

For more information, visit our common diagnostic tests page.

If your esophagus shows signs of damage, your doctor will remove a small sample of tissue (biopsy) that will be examined under a microscope to confirm a diagnosis. The biopsy also will be used to check for signs of cancer or precancerous changes (dysplasia).

If the biopsy confirms the presence of Barrett’s esophagus without the presence of precancerous cells, your doctor likely will recommend that you have periodic repeat endoscopies to continually monitor for any signs of esophageal cancer. This is done as a precaution because cancer can develop years after diagnosing Barrett’s esophagus.

No medications can reverse Barrett’s esophagus, but there are things you can do to improve acid reflux symptoms and slow the development of Barrett’s esophagus. Your treatment will vary depending on whether your doctor found precancerous or cancerous cells during your biopsy.

If your biopsy did not show cancerous cells, your treatment may consist mainly of lifestyle and diet changes to reduce and control acid reflux, including:

- Limiting fatty and spicy foods, chocolate, and caffeine

- Reducing intake of alcohol

- Avoiding tobacco use

- Losing weight

Your doctor also may prescribe medications to reduce the amount of acid your stomach produces (proton pump inhibitors) or recommend antacids after meals and at bedtime.

If cancerous cells were found in your biopsy, various treatment options are available, including the surgical removal of your esophagus (esophagectomy).

Surgery may not be an option for some people, so if your doctor or cardiothoracic surgeon think surgery is not right for you, other treatment options are available as outlined below.

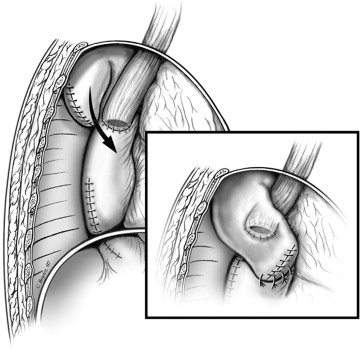

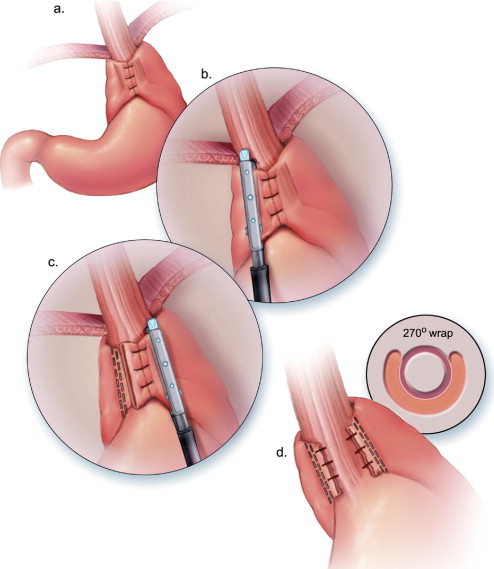

A procedure called Nissen fundoplication may be considered for patients who do not want to take lifelong medications or who are concerned about side effects, like osteoporosis, when the medications are not controlling their symptoms. The procedure also may be considered for patients whose stomach has pushed up through the diaphragm and into the chest (hiatal hernia).

A procedure called Nissen fundoplication may be considered for patients who do not want to take lifelong medications or who are concerned about side effects, like osteoporosis, when the medications are not controlling their symptoms. The procedure also may be considered for patients whose stomach has pushed up through the diaphragm and into the chest (hiatal hernia).

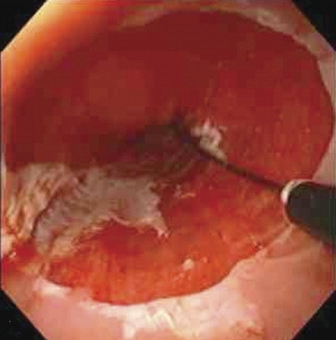

Uses an endoscope to remove superficial abnormalities (Barrett’s esophagus, dysplasia, and very early cancers) limited to the inner lining of the esophagus (mucosa)

Uses an endoscope to remove superficial abnormalities (Barrett’s esophagus, dysplasia, and very early cancers) limited to the inner lining of the esophagus (mucosa)

Uses heat to destroy abnormal esophageal tissue (Barrett’s esophagus as long as there is no suspicion of dysplasia or cancer); may be recommended after endoscopic resection

Uses heat to destroy abnormal esophageal tissue (Barrett’s esophagus as long as there is no suspicion of dysplasia or cancer); may be recommended after endoscopic resection

Uses an endoscope to apply a cold liquid or gas to abnormal cells in the esophagus. The cells are allowed to warm up and then are frozen again. The cycle of freezing and thawing damages the abnormal cells.

Uses an endoscope to apply a cold liquid or gas to abnormal cells in the esophagus. The cells are allowed to warm up and then are frozen again. The cycle of freezing and thawing damages the abnormal cells.

Destroys abnormal cells by making them sensitive to light

Destroys abnormal cells by making them sensitive to light

Most endoscopic treatments are performed as an outpatient (a patient who receives treatment but is not hospitalized overnight). Laparoscopic antireflux surgery usually requires a 1-2 night hospital stay with full recovery in 3-4 weeks.

If you undergo an esophagectomy, you should expect to spend approximately 7 days in the hospital. You should expect recovery to take about 6 to 8 weeks. Most patients eventually return to normal activities. If your job requires heavy lifting, your doctor may recommend that you take about 3 months off work following surgery; however, if your job is less strenuous, you may be able to go back to work in about 6 to 8 weeks. Be sure to discuss your specific recovery with your doctor before the surgery, and at any follow-up appointments

You also will need to adjust your eating after the surgery. Most patients benefit from eating smaller, more frequent meals after esophagectomy because you tend to feel full very quickly.

Patients also should avoid eating for 3 hours before sleeping and should sleep at a 30° angle using pillows or a foam wedge to help prevent stomach contents from coming up and getting into the lungs.

Some patients may experience nausea, vomiting, cramping, flushing (blushing; redness of the skin), or diarrhea when their stomachs become overly full (distended); limiting liquids with your meals may help reduce these symptoms. Sweets, such as candy, sugar, syrups, and honey also may contribute to this problem. If you experience any problems while eating, speak with your doctor.

People with Barrett’s esophagus also have an increased risk of developing esophageal cancer.

Although the risk is small, it is important to have regular checkups with your doctor to monitor your condition. Please see our page on esophageal cancer for more information.

Reviewed by: Robbin G. Cohen, MD, with assistance from John Hallsten and Travis Schwartz

July 2016

Previously reviewed by: Jules Lin, MD , and Rishindra Reddy, MD