- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

September 14, 2016

The aortic valve functions as the gate between the heart and the body. The valve normally has three very thin and movable cusps that open to let blood pass through when the heart squeezes and then close in between heart beats to keep pumped blood from moving backward into the heart (visit Aortic Valve Disease for more information).

The most common disease of the aortic valve is called aortic stenosis. It occurs when the cusps of the aortic valve become stiff and covered with calcium, making them less movable and narrowing the passageway through which blood is pumped to the body. It’s like having a clogged faucet at the outlet of the heart, causing the heart to work harder in order to pump blood. The only effective treatment is to replace the aortic valve. Once symptoms like chest pain, shortness of breath, or fainting occur, most patients will die within a few years if the valve is not replaced.

Heart surgeons have been replacing aortic valves with excellent results for more than 50 years. In fact, surgical aortic valve replacement (also called SAVR) is one of the most common operations performed by heart surgeons around the world. The operation has traditionally involved making an incision in the chest to get access to the heart and aorta, as well as stopping the heart with the use of the heart-lung machine (cardiopulmonary bypass). Most patients spend 4 or 5 days in the hospital after aortic valve replacement, and the recovery period is approximately 6 weeks.

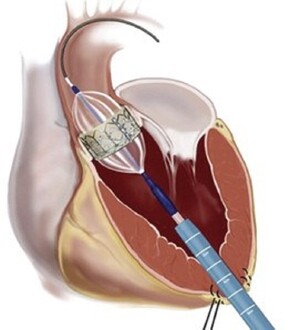

The wonders of engineering and modern technology now make it possible to replace the aortic valve in select patients without opening the chest and without stopping the heart. The new procedure, called transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), is performed by a team of cardiologists and heart surgeons. Instead of going directly through the chest, surgeons open the diseased valve with a balloon on a catheter placed through a large artery in the groin. This is followed by placement of a new valve that is also delivered on a catheter. As you can imagine, the potential for less pain, a shorter hospital stay, and a quicker recovery is substantial.

Because SAVR results are excellent and the long-term results of TAVR are still unknown, TAVR was originally restricted to patients who were too ill to undergo heart surgery. In fact, every potential TAVR patient in the United States must be evaluated by a cardiologist and two heart surgeons (the “heart team”) in order to determine who should get TAVR and who should get SAVR. Because early results have been promising, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved TAVR for both high-and intermediate-risk patients.

Figuring out a patient’s “risk” for aortic valve surgery can be complicated and usually involves a calculation from The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) National Database. The Database contains information from millions of patients used to create risk models that allow surgeons and cardiologists to calculate the predicted risk of death and complications with SAVR for an individual patient. This is accomplished by using the STS Risk Calculator and inputting information, such as age, kidney and lung function, and whether a previous stroke or heart attack has occurred. The heart team also takes other things into account, like whether patients are frail or have issues that may not be included in the STS Database that would keep them from recovering from surgery normally. Patients who should undergo SAVR are low-risk patients (low STS risk score), patients with two aortic cusps instead of three (bicuspid aortic valve), patients who need coronary artery bypass or surgery on more than one heart valve, or patients whose primary aortic valve problem is leakage (aortic insufficiency) and not stenosis.

Obviously, no one wants to have open heart surgery if they don’t have to or if there is a less invasive alternative. The important thing to remember is that your heart team will do its best to find the right treatment for every patient, whether it be SAVR or TAVR.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons.