- Adult Heart DiseaseDiseases of the arteries, valves, and aorta, as well as cardiac rhythm disturbances

- Pediatric and Congenital Heart DiseaseHeart abnormalities that are present at birth in children, as well as in adults

- Lung, Esophageal, and Other Chest DiseasesDiseases of the lung, esophagus, and chest wall

- ProceduresCommon surgical procedures of the heart, lungs, and esophagus

- Before, During, and After SurgeryHow to prepare for and recover from your surgery

What is an Aortic Dissection?

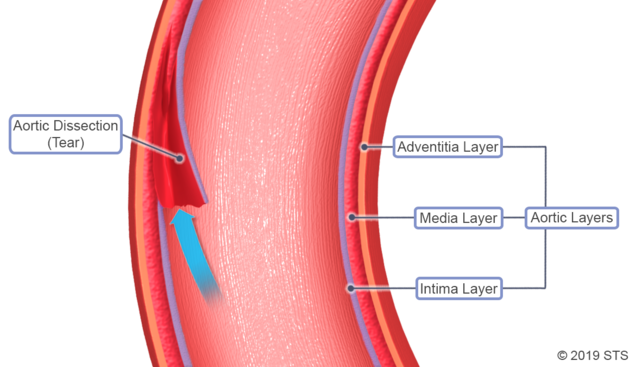

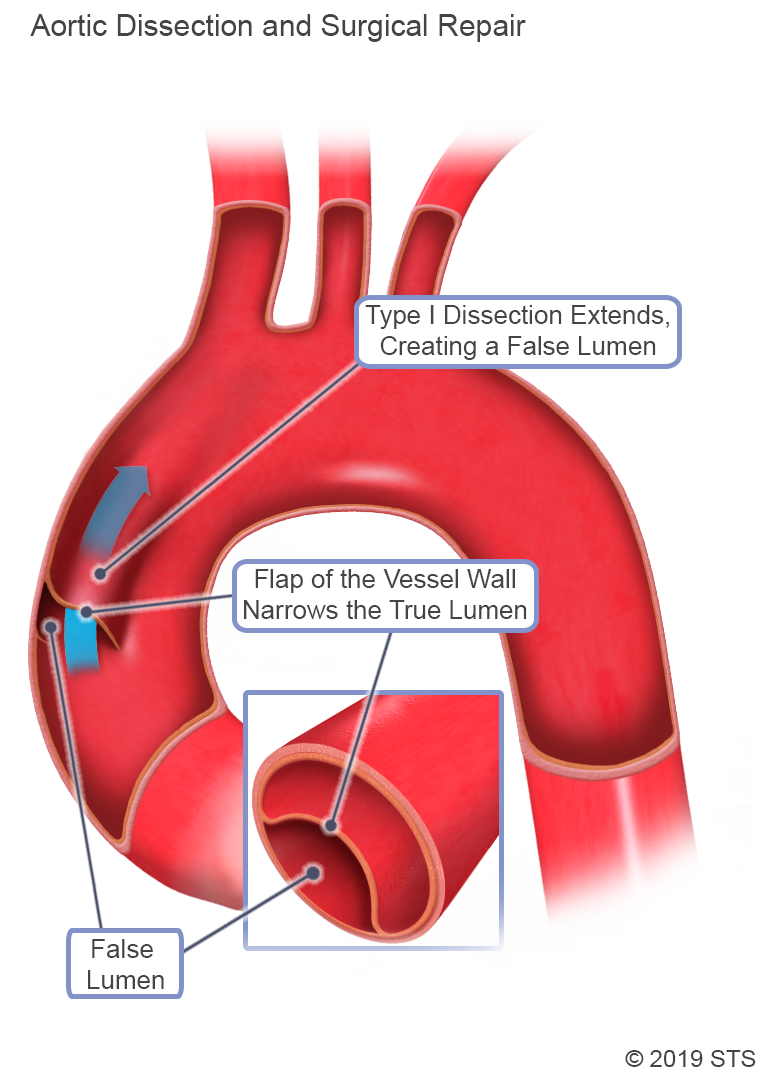

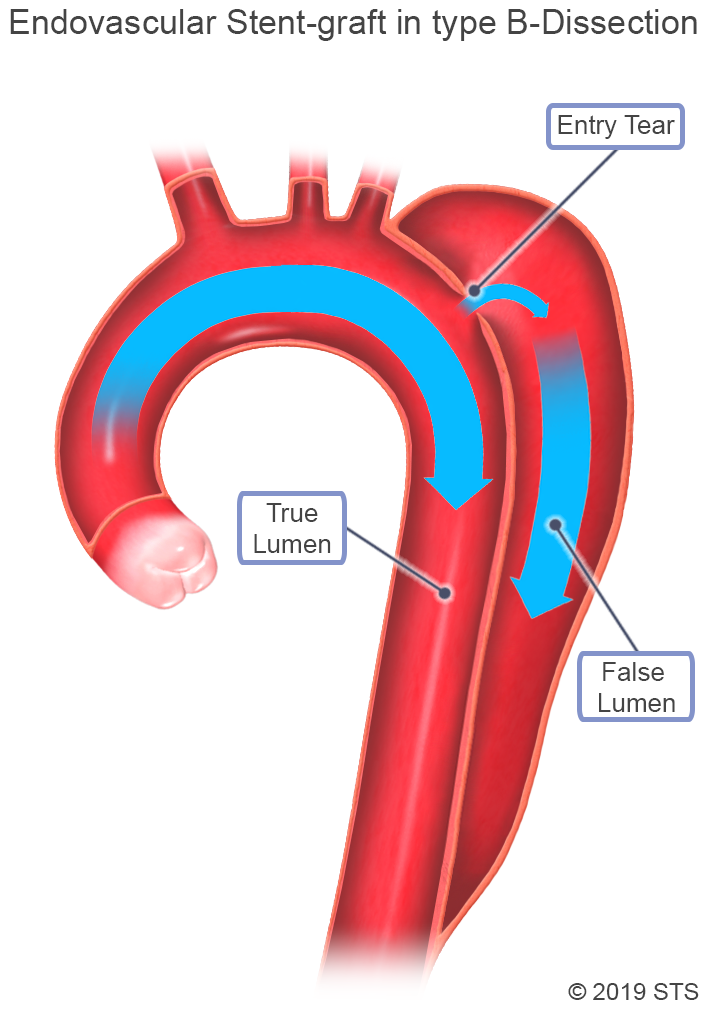

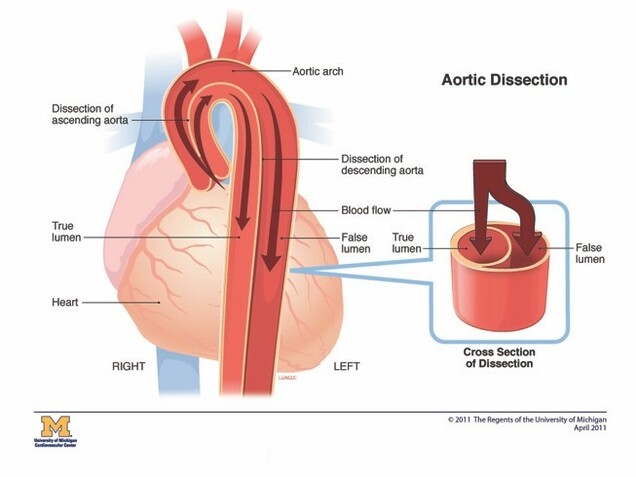

Aortic dissection occurs when the innermost layer of the aorta (intima) tears and blood flows between the layers of the aorta's wall.

Consider the following analogy: the aorta is like an unopened roll of paper towels. The cardboard would be the intima, the innermost layer of the aorta through which blood flows. The layers of paper towels would be the muscle and connective tissue surrounding the intima (media layer). The plastic wrapper around the paper towels would be the added strength layer (adventitia layer).*

Using the paper towel analogy to describe an aortic dissection, a tear would occur in the cardboard tube, causing the blood to plow through both the cardboard and paper towels, where it would create a false channel. The blood would either be contained by the plastic wrapper or the plastic wrapper would burst (i.e., the aorta ruptures).

* Credit for the “paper towel” analogy: Dr. Thomas E. MacGillivray, cardiac surgeon and Chief of Cardiac Surgery and Thoracic Transplant Surgery at Houston Methodist Hospital.

The aorta has several different parts:

- Aortic root

- Ascending aorta

- Aortic arch

- Descending thoracic aorta

- Abdominal aorta

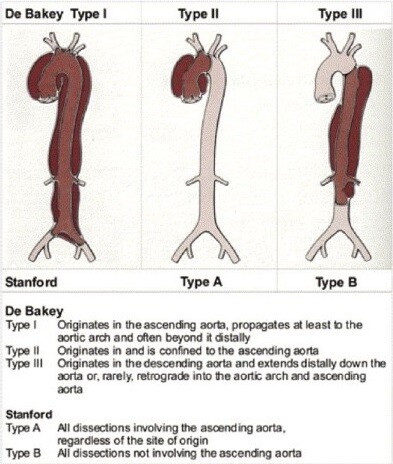

Aortic dissection can occur in any parts of the aorta. Aortic dissections are classified according to the location of the initial aortic tear, and the parts of the aorta that are involved in the dissections. The two major classifications are the Stanford Classification and the DeBakey Classification.

Why do people get an aortic dissection?

Aortic dissection may occur for several reasons, including chronic high blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking, illegal drug use, trauma, and genetics.

Chronically uncontrolled high blood pressure can put stress on the aortic wall and over time can lead to aneurysm (a weakening in the wall which causes it to “balloon” or expand in size) and dissection. Patients with blood vessel disease related to years of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking can develop a calcification or ulcers of the aorta that may become the site where a dissection occurs.

Drugs that increase the blood pressure, such as cocaine, crack, and methamphetamines also can increase the likelihood of an aortic dissection. In addition, the aorta can dissect or rupture from trauma, such as during a high-speed motor vehicle accident or fall from a significant height.

Some people are born with an alteration in specific genes that affect development of the aortic wall and predispose the aorta to enlargement and/or dissection. Syndromes that are associated with certain genetic defects include:

- Marfan Syndrome

- Loeys-Dietz Syndrome

- Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

- Familial Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm

A bicuspid aortic valve is a marker for a connective tissue syndrome and may be associated with valve problems, aortic root aneurysms, and ascending aortic aneurysms. These aneurysms have the potential to result in aortic dissection.

How do I know that I have an aortic dissection?

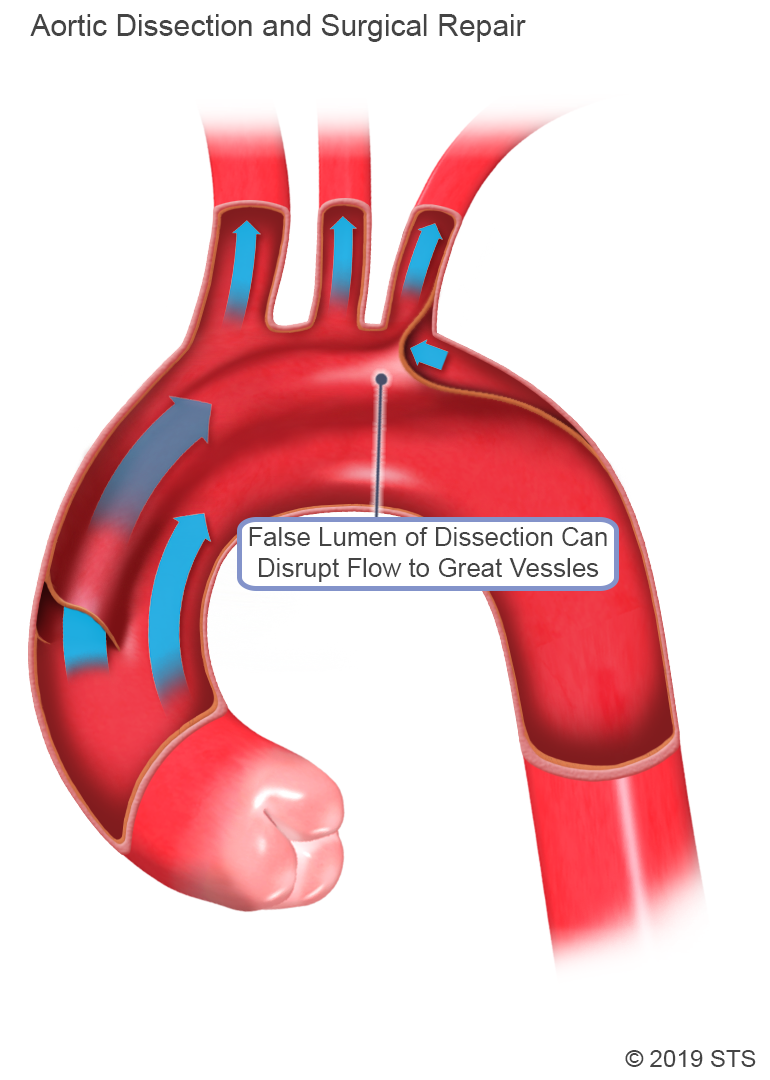

The most common symptom is severe pain, often described as a tearing or ripping feeling in the chest. The pain may radiate to the back or move down toward the abdomen. Because an aortic dissection can impede blood flow to any of the blood vessels that branch from it or even affect the aortic valve, you also can experience various other symptoms that would not necessarily lead you or your physician to suspect a problem with the aorta.

If the arteries that supply blood to the heart (coronary arteries) are affected, you would have chest pain that may seem like a heart attack. If the branches to the brain (carotid arteries) are affected, you would have symptoms of stroke, such as difficulty with speech, inability to move one side of your body, or loss of consciousness.

If the branches to the arms or legs (subclavian or iliofemoral arteries) are affected, you could develop numbness, tingling or pain in your arm(s) or leg(s), or inability to move your arm(s) or leg(s).

If the artery to your intestines (superior mesenteric artery) is affected, you may have nausea, abdominal pain, or bloody bowel movements.

If the arteries to your spinal cord (intercostal and lumbar arteries) are affected, you might not be able to move your legs (paraplegia). Blood flow to the liver and kidneys also can be affected; this would not necessarily cause symptoms but would show up in laboratory studies from a blood sample. Additionally, if the aortic valve becomes severely leaky because of the dissection, you might feel like you can’t breathe, which is a sign of heart failure.

When aortic dissection is suspected, time is of the essence. You usually will be sent for an emergent computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous contrast (a dye injected via a vein) so that doctors can look at blood flow in your aorta.

If an aortic dissection is present, the CT scan will show blood flowing in the false channel and indicate the part(s) of the aorta involved in the dissection. A transesophageal echocardiogram, with the ultrasound probe placed in the esophagus behind the heart and aorta, sometimes is performed to look for the dissection in the ascending or descending thoracic aorta.

For more information on these tests, visit our common diagnostic tests page.

What are the treatment options?

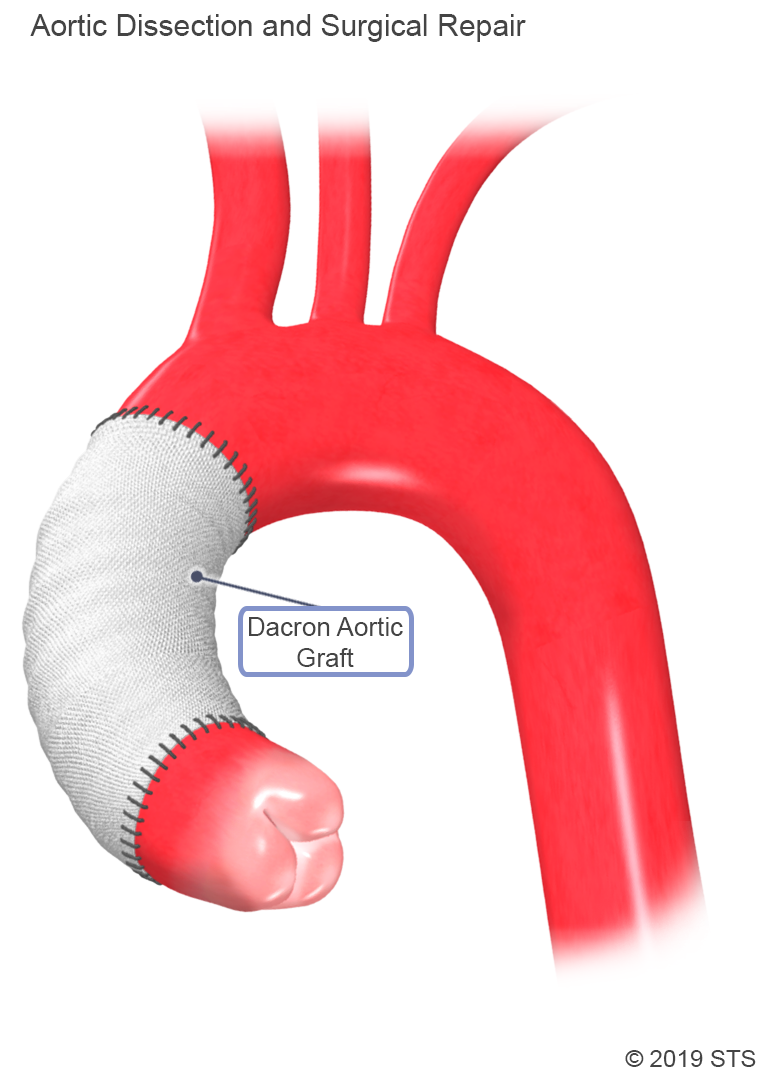

When an aortic dissection involves the aortic root or ascending aorta (Stanford Type A or DeBakey Types 1 and 2), the treatment is emergency surgery. The risk of death from aortic rupture increases with every hour from the onset of symptoms. The patient should undergo emergent open heart surgery. Sometimes this will require a transfer to a hospital that performs the procedure.

The operation is done via an incision down the middle of the chest, through the breastbone (median sternotomy). The heart-lung machine is used to bypass the heart and lungs, which are stopped during the operation. Sometimes the body temperature is cooled (to as low as 64° Fahrenheit, called deep hypothermic circulatory arrest) in order to temporarily stop blood flow so the aortic arch–the part of the aorta that gives off the arteries to the brain–can be repaired. The ascending aorta is replaced with a synthetic woven tube graft. Sometimes the aortic root and aortic valve need to be replaced, or all of the aortic arch.

Possible complications after this operation include:

-Bleeding requiring transfusion or re-operation

-Stroke

-Delirium

-Heart dysfunction or heart attack

-Being on the ventilator for several days or longer (respiratory failure)

-Kidney failure, requiringPossible hemodialysis

-Paralysis or paraplegia

-Death

When an aortic dissection involves the aortic root or ascending aorta (Stanford Type A or DeBakey Types 1 and 2), the treatment is emergency surgery. The risk of death from aortic rupture increases with every hour from the onset of symptoms. The patient should undergo emergent open heart surgery. Sometimes this will require a transfer to a hospital that performs the procedure.

The operation is done via an incision down the middle of the chest, through the breastbone (median sternotomy). The heart-lung machine is used to bypass the heart and lungs, which are stopped during the operation. Sometimes the body temperature is cooled (to as low as 64° Fahrenheit, called deep hypothermic circulatory arrest) in order to temporarily stop blood flow so the aortic arch–the part of the aorta that gives off the arteries to the brain–can be repaired. The ascending aorta is replaced with a synthetic woven tube graft. Sometimes the aortic root and aortic valve need to be replaced, or all of the aortic arch.

Possible complications after this operation include:

-Bleeding requiring transfusion or re-operation

-Stroke

-Delirium

-Heart dysfunction or heart attack

-Being on the ventilator for several days or longer (respiratory failure)

-Kidney failure, requiringPossible hemodialysis

-Paralysis or paraplegia

-Death

When an aortic dissection involves the descending thoracic aorta (Stanford Type B or DeBakey Type 3), several different management strategies may be used. You may be monitored closely in an intensive care unit (ICU) with intravenous (IV) infusions of medications to aggressively lower your heart rate and blood pressure. This helps decrease stress on the aorta to prevent it from rupturing and also helps promote flow through the “cardboard tubing” rather than the “paper towel layers.” Many patients with a dissection in the descending thoracic aorta will not require emergency surgery and can initially be managed with medications.

When an aortic dissection involves the descending thoracic aorta (Stanford Type B or DeBakey Type 3), several different management strategies may be used. You may be monitored closely in an intensive care unit (ICU) with intravenous (IV) infusions of medications to aggressively lower your heart rate and blood pressure. This helps decrease stress on the aorta to prevent it from rupturing and also helps promote flow through the “cardboard tubing” rather than the “paper towel layers.” Many patients with a dissection in the descending thoracic aorta will not require emergency surgery and can initially be managed with medications.

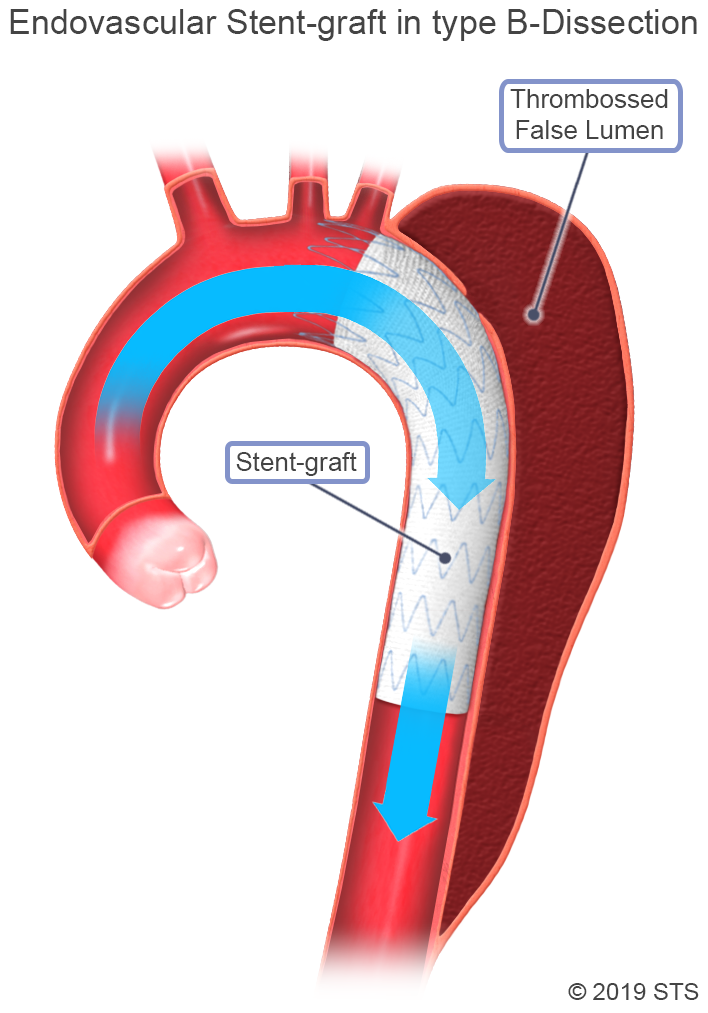

You also may undergo an emergent or urgent procedure known as Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair (TEVAR), in which a stent graft, consisting of fabric sewn onto an expandable nitinol (nickel-titanium metal alloy) frame, is placed in the descending thoracic aorta to cover the intimal tear and prevent blood from flowing into the false channel. The TEVAR procedure is less invasive and may be used instead of open surgery in some patients. Ask your surgeon if you are a candidate for TEVAR. Younger patients and those with connective tissue disorders are often not candidates for TEVAR.

Possible complications after this operation include:

-Stroke

-Temporary or permanent paralysis

-Bleeding complication from accessing the femoral arteries in the groin

-Kidney dysfunction or failure related to impaired blood flow to the kidney arteries from the dissection or related to the contrast given for the CT scan or the stent graft procedure

-Tear extending backward to the arch or ascending aorta (retrograde dissection), requires emergency surgery

-Death

You also may undergo an emergent or urgent procedure known as Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair (TEVAR), in which a stent graft, consisting of fabric sewn onto an expandable nitinol (nickel-titanium metal alloy) frame, is placed in the descending thoracic aorta to cover the intimal tear and prevent blood from flowing into the false channel. The TEVAR procedure is less invasive and may be used instead of open surgery in some patients. Ask your surgeon if you are a candidate for TEVAR. Younger patients and those with connective tissue disorders are often not candidates for TEVAR.

Possible complications after this operation include:

-Stroke

-Temporary or permanent paralysis

-Bleeding complication from accessing the femoral arteries in the groin

-Kidney dysfunction or failure related to impaired blood flow to the kidney arteries from the dissection or related to the contrast given for the CT scan or the stent graft procedure

-Tear extending backward to the arch or ascending aorta (retrograde dissection), requires emergency surgery

-Death

What is the recovery like after surgery?

For an ascending aortic dissection, the course and length of your recovery would depend on your condition at the time of surgery, the extent of the operation, and any post-operative complications. The hospital stay may vary from 5-7 days to 3-4 weeks.

For a medically managed dissection that involves the descending thoracic aorta and abdomen, your hospital stay would be 5-7 days to make sure that your blood pressure is well-controlled and the aorta is not changing on follow-up imaging. If the dissection is treated with a stent graft, the hospital stay could vary from 5-7 days to a few weeks, depending on whether you have post-operative complications.

What happens after discharge from the hospital?

Regardless of what part of the aorta is involved, if you have an aortic dissection, you will need lifelong surveillance to monitor for post-operative complications or continued growth or change in the aorta. Surveillance imaging may include CT scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Follow-up is usually with a cardiothoracic surgeon who will review the imaging and determine what, if any, further procedures need to be performed. A typical follow up plan would be to see your surgeon at 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, and then once a year with a CT scan or MRI at each visit. Sometimes more frequent visits are needed.

In addition, you will need to see your primary care physician and cardiologist regularly to make sure your blood pressure is well-controlled. This often requires taking several medications. Modifying your activity or exercise is recommended, including avoiding heavy lifting and prolonged straining. If you smoke or do drugs, you should quit. Your primary doctor can prescribe medications that will help you quit smoking.

Read more information about before heart surgery, day of heart surgery, and after heart surgery.

What can I do to prevent it?

If you have an aneurysm, this can be monitored appropriately or treated before an aortic dissection occurs. Blood pressure control is important, and you should work with your primary care physician or cardiologist to adjust your medications. Modifying your activities and exercise to avoid heavy weight lifting and prolonged straining is also recommended. Avoid smoking to prevent injury to the blood vessel wall of the aorta and its branches.

If you or someone in your immediate family has been diagnosed with a genetic syndrome (Marfan Syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Loeys-Dietz Syndrome, familial thoracic aortic aneurysm, bicuspid aortic valve,) or you have a family history of thoracic aortic aneurysm or aortic dissection, you should see a cardiologist or cardiothoracic surgeon to undergo screening with CT angiography (CTA) to see if you have an aortic aneurysm.

Reviewed by: Kendra J. Grubb, MD, MHA

March 2019